Deep Dive into Yann LeCun’s JEPA

- Relevant Talks by Yann LeCun

- Problems with Current AI

- Modality

- A Framework for Building Human-Level AI

- Actor

- Cost

- Configurator

- World Model

- Data Streams

- Objective Driven AI

- Towards Implementing JEPA

- I-JEPA: Self-Supervised Learning from Images with a Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture

- V-JEPA: Revisiting Feature Prediction for Learning Visual Representations from Video

- MC-JEPA: A Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture for Self-Supervised Learning of Motion and Content Features

- What’s Next?

- V-JEPA 2

[2025-07-04 Added section on V-JEPA 2]

In the AI research community, Yann LeCun has a unique and often controversial perspective. As of 2024, LLMs and Generative AI are the main focus areas of the field of AI. We’ve all been impressed by the performance of LLMs in various contexts, and generative systems like OpenAI’s Sora. However, it is not clear where these advances fit in the long term goal of achieving and surpassing human level intelligence, which many call AGI.

In his position paper A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence and his many recent talks (linked below), Yann presents an alternative framework for achieving artificial intelligence. He also proposes a new architecture for a predictive world model: Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture (JEPA).

This blog post will dive deep into Yann’s vision for AI, the JEPA architecture, current research, and energy-based models. We will go deep into the technical aspects of these ideas, as well as give my opinions, along with interesting references. I will also cover recent research advances such as V-JEPA

This is a long post, feel free to jump to the sections about JEPA, I-JEPA, and V-JEPA.

Relevant Talks by Yann LeCun

From Machine Learning to Autonomous Intelligence

Objective-Driven AI: Towards Machines that can Learn, Reason, and Plan

Problems with Current AI

The JEPA architecture aims to address current AI challenges. To contextualize these issues, we’ll examine Yann LeCun’s criticisms of popular AI trends as of 2024.

Recent years have seen tremendous excitement around Large Language Models (LLMs) and Generative AI. LLMs are pretrained using autoregressive self-supervised learning, predicting the next token given preceding ones. They’re trained on vast datasets of text and code from the internet and books, often fine-tuned with supervised learning or reinforcement learning. Generative AI broadly refers to creation of multimodal media from inputs, such as text-to-image generation.

However, these models face significant limitations:

- Factuality / Hallucinations: When uncertain, models often generate plausible-sounding but false information. They’re optimized for probabilistic likelihood, not factual accuracy.

- Limited Reasoning: While techniques like Chain of Thought prompting improve LLM’s ability to reason, they’re restricted to solving the selected type of problem and approaches to solving them without improving generalized reasoning abilities.

- Lack of Planning: LLMs predict one step at a time, lacking effective long-term planning crucial for tasks requiring sustained goal-oriented behavior.

Despite impressive advancements, the challenge of autonomous driving illustrates the gap between current AI and human-level intelligence. As LeCun notes, humans can learn driving basics in about 20 hours. In contrast, self-driving car development has consumed billions of dollars, extensive data collection, and decades of effort, yet still hasn’t achieved human-level performance.

Even achieving Level 5 autonomy wouldn’t signify true human-level AI or Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). Such intelligence would involve learning to drive from scratch within a day, using only data collected during that experience, without relying on massive pre-existing datasets for finetuning. Realizing this level of adaptable intelligence might require several more decades of research.

Common Sense

The limitations in AI models can often be attributed to a lack of common sense. Common sense can be defined as thinking and acting in a reasonable manner. Humans and many animals have this ability. This includes avoiding egregiously dangerous or incorrect actions. Expanding on the autonomous driving example, AV systems need to be trained to deal with new situations safely. When learning to drive, humans utilize their common sense to know to not do dangerous things like driving off the road or into other cars. This is not obvious to current AV systems, so they require a large amount of training data to avoid these actions.

LLMs similarly demonstrate a lack of common sense through nonsensical or illogical outputs. Common sense is a vague term. One definition is that it is a lower bound on the types of errors an agent makes. For AI to be trustworthy, it needs this foundational level of understanding.

Common sense can also be viewed as a collection of world models. These models enable quick learning of new skills, avoidance of dangerous mistakes in novel situations, and prediction of outcomes in unfamiliar scenarios. Essentially, we use world models to generalize our experiences.

How Humans Learn

Humans acquire a basic understanding of the world during early infancy, but we’re also born with some innate knowledge. The brain isn’t randomly initialized; it’s evolved, pre-trained, and fine-tuned throughout life. This differs significantly from artificial neural networks, which start with random initializations and have far weaker inductive biases than humans or animals. Life is generally pre-programmed to behave in a certain way from birth. More intelligent life is able to learn more and not purely rely on innate knowledge.

Understanding the extent to which babies acquire common sense during infancy is crucial for AI development. If common sense is largely innate, the focus should be on massive datasets mimicking evolutionary timescales. If it’s primarily learned, priority should be given to models that excel at quick learning from limited data.

A baby’s experience, while not comparable to evolutionary timescales, still represents a substantial dataset. If a baby is awake for 8 hours a day, in four months they have seen about 960 hours of data. This data is also augmented by other sensory signals and dense biological supervision (pain, hunger, emotions). This is around the same length as the Kinetics 400 video dataset. This is still dwarfed by the millions of hours of video that self driving cars are using.

This Nature paper by Orhan and Lake explores learning from infant-perspective data. They demonstrate that computer vision models can be trained on noisy, less diverse datasets collected from infant headcams. These egocentric datasets are far noisier and less diverse than standard image/video datasets, but AI models without strong inductive biases can learn from them.

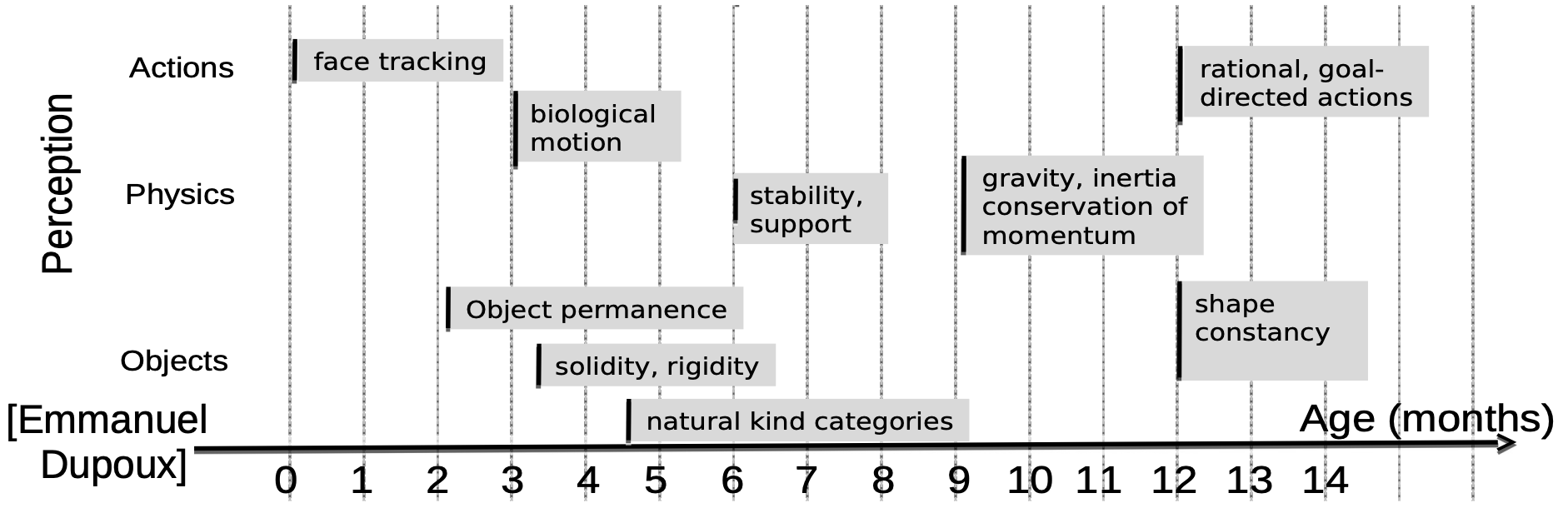

Emmanuel Dupoux’s diagram, presented by Yann LeCun, suggests that babies often understand concepts like object permanence, solidity, and biological motion by around four months. While presented as quick learning, it’s important to note the significant amount of data processing that occurs during this time.

We don’t yet know precisely how much data AI systems would need to learn the same concepts as babies. It’s likely that the data efficiency gap is relatively small for basic concepts that babies learn. For instance, object permanence could probably be learned from 960 hours of video data. However, it becomes evident that this gap grows substantially with age and with the complexity of the knowledge being assessed. The challenges in developing fully autonomous vehicles clearly demonstrate how large this data efficiency gap can become.

In addition to the lack of common sense, we mention three other fundamental gaps in the ability of current AI: hallucinations, lack of planning, and lack of reasoning.

Learning to Think

The question of whether Large Language Models (LLMs) can truly reason and plan is a contentious topic in the AI community. While these models exhibit behaviors that resemble reasoning and planning, skeptics argue that they merely replicate patterns from their training data.

To frame this discussion, let’s consider reasoning and planning as forms of “thinking”, which we will define as a variable length internal process that precedes any outputs.. Current deep learning models employ two primary mechanisms for this kind of processing:

- Depth: Each layer in a neural network can be viewed as a step in the thinking process. However, this depth is typically fixed, with some recent work exploring dynamic depth adjustment based on input complexity. Despite these advances, maximum depth and other constraints still limit the model’s flexibility.

- Sequential Generation: Decoder-based LLMs, such as GPT, generate text one token at a time. Each step in this process involves some degree of computation that could be interpreted as thinking. Prompt engineering techniques leverage this sequential nature to guide the model towards desired outputs. A key limitation of this approach is that the model must produce a token at each step, preventing purely internal information processing.

While these properties enable models to create the illusion of thought, significant advancements are necessary to achieve more effective reasoning and planning capabilities.

Many researchers draw parallels between AI and the two-system model of thinking proposed by Daniel Kahneman. System 1 thinking is fast and intuitive, providing immediate responses without conscious deliberation. System 2, in contrast, is slower and more deliberate, engaging in deeper cognitive processing. Current machine learning models, including LLMs, primarily operate in a System 1 mode by processing information in a single pass without the ability to plan ahead. While they excel at pattern recognition, they lack true reasoning or planning capabilities.

This inability to plan contributes to factual errors in LLM outputs. Each generated word carries a risk of inaccuracy, with the probability of errors increasing exponentially as the output length grows. The sequential nature of token generation means that early mistakes can compound, potentially invalidating the entire output. This stands in stark contrast to human speech, where we typically plan our utterances at a higher level before vocalization, minimizing such errors. In this context, reasoning can be viewed as the planning of speech. Without the capacity to reason or plan effectively, LLMs essentially “speak without thinking.”

In the JEPA paper, Yann LeCun proposes frameworks for models that can think. Learning to think may address the fundamental problems in current AI models and represent a crucial step towards achieving more human-like intelligence in AI.

Modality

Recent advancements have expanded LLMs to include multimodal processing and outputs, but they remain primarily language-centric. This raises questions about the sufficiency of language alone for AI and the investment needed in visual understanding. Could visual comprehension help ground AI in reality, improving common sense and reducing hallucinations?

Language serves as a compressed representation of the complex concepts humans experience. Its expressive power is vast, capable of describing intricate scientific theories and nuanced emotions. Yet, language alone may not suffice for complete understanding.

Humans interpret language within the context of shared reality. It functions as a highly efficient medium for transmitting information through the relatively narrow bandwidth of speech. When we process language, our brains rely on prior knowledge and experiences. While some of this prior information can be acquired through text, a significant portion stems from visual and physical interactions with the world.

Currently, it does seem that language models are more capable than vision models. Language models currently outperform visual models due to information density, data requirements, and data availability.

In a given data point there is a certain amount of explicit information in the form of bits. But then there is relevant information that is useful. For example, if you take an image of the park, a lot of bits are used to represent the position of every blade of grass. But that is not useful in most scenarios. Language is very compressed. While there are some filler words that don’t add much information, the ratio of knowledge to bits is high. However, for images, most of the bits are not useful. This means you need orders of magnitude more bits of data to learn equivalent knowledge. Video models are further behind because you need another order of magnitude more bits since consecutive frames in video are mostly redundant.

While language-based AI leads, scenarios exist where visual learning could catch up. One scenario in which visual learning could overtake language is that we will have a large number of robots / autonomous vehicles interacting with the world while collecting visual data. Language will be data constrained with the rate of new text generation limiting scaling. In a world with a lot of robots, the knowledge gained from the visual world and the size of the available datasets may exceed that of text. However, this is all very speculative. We don’t know how important vision or grounding is for intelligence.

A Framework for Building Human-Level AI

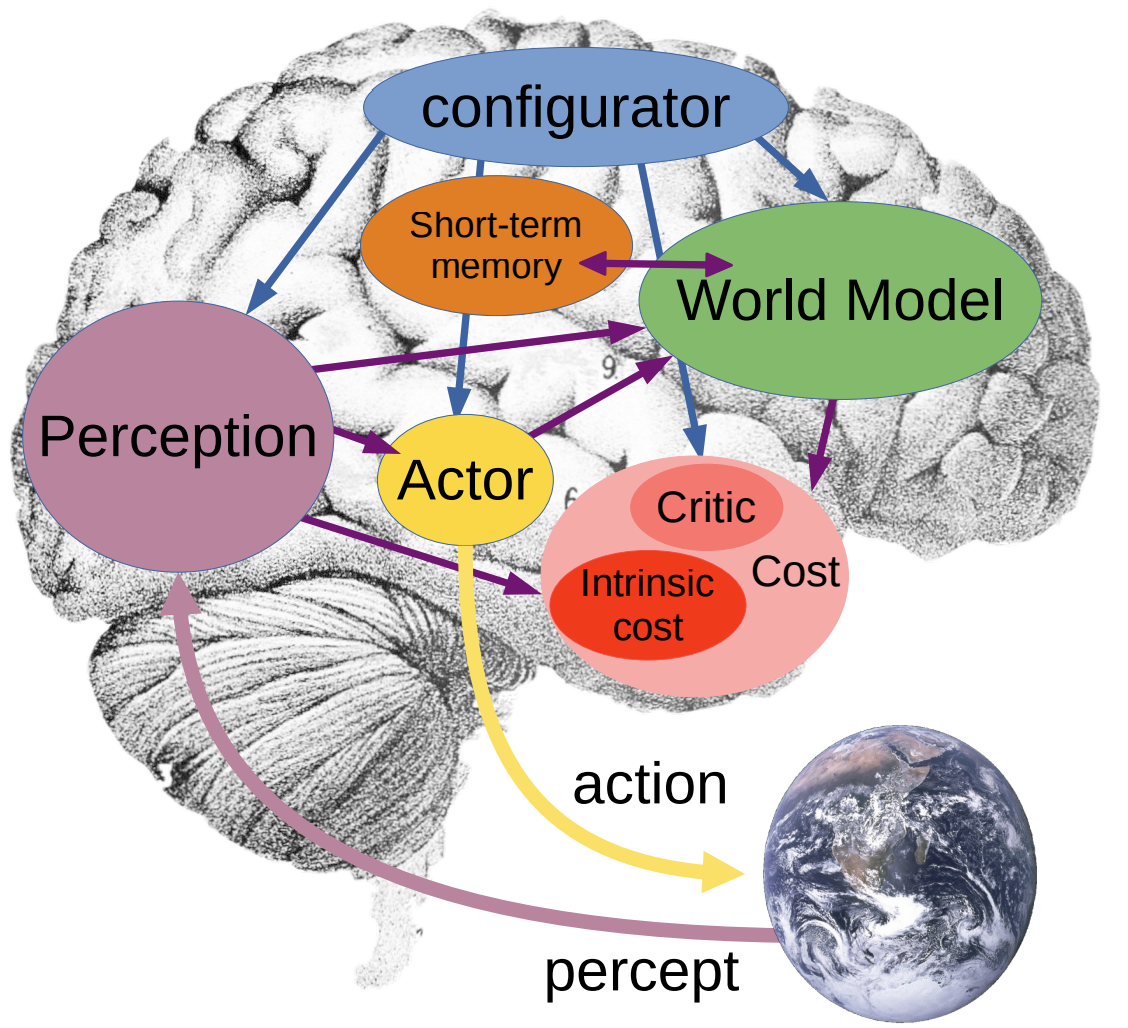

Yann proposes a high level architecture for building an AI system that is aimed at addressing the problems we outlined. This is a design for an intelligent agent that can perceive the world,

We will then explore the various challenges that must be addressed to construct such an architecture. Currently, this is merely a theoretical architecture. Building certain components remains an open problem, and assembling all the modules will pose an additional challenge.

This architecture contains different proposed components. We will explain these components and their relationships.

Configurator: Configures input from all other modules and configures them for the task at hand. It tells the perception module what information to extract.

Perception: Estimates the current state of the world from different sensory signals.

World module: Estimates missing information about the state of the world and predicts future states. It simulates the world and extracts relevant information as determined by the configurator.

Cost module: Measures the level of discomfort as energy. This energy is the sum of the intrinsic cost module and the trainable critic module.

Intrinsic cost: Computes a cost given the current state of the world and predicted future states. This cost can be imagined as hunger, pain, or general discomfort. This cost can be hardwired in AI agents, as done with rewards in RL.

Trainable Critic: Predicts future intrinsic energy. It has the same input as the intrinsic cost. This estimate is dependent on the intrinsic cost and cannot be hardwired. It is trained from past states and subsequent intrinsic cost, retrieved from memory.

Short term memory: Stores relevant information about past present and future states of the world along with intrinsic cost.

Actor: Proposes sequences of actions. These sequences are executed by the effectors. The world model predicts future states from the sequence which then generates a cost.

Actor

The actor proposes an optimal action or sequence of actions.

If the world model and cost are well behaved, gradient based optimization can be used to determine an optimal action sequence. If actions are discrete then dynamic programming methods such as beam search can be used.

There are two different modes in the actor. These align with Kahneman’s System 1 and 2, which we mentioned earlier.

Mode 1 Reactive Behavior: A policy module that computes an action from the state generated by perception and short-term memory. This module acts fast and produces simple decisions. A world model is needed to estimate the cost of an action. Without a world model the agent would have to perturb their actions which is not feasible. The world model can be adjusted after observing the next state.

Mode 2 Reasoning and Planning: A sequence of actions along with predicted corresponding states is generated. From this sequence of states, a cost can be computed. Planning is done by optimizing the action sequence to minimize total cost. The action sequence is then sent to the effectors which execute at least the beginning of the sequence. The states and costs are stored in short-term memory. The sequence can be optimized through gradients since the cost and world model are differentiable. Dynamic programming can also be used. Planning in this setup is essentially inference time cost optimization.

Agents may have multiple policy modules executing mode 1. In this design, the agent only has one world model, so mode 2 can only be run once. However, AIs could be designed to have multiple world models and mode 2 processes at the same time. This is similar to having multiple thoughts at the same time. However, this would be very complicated in that the different modules would have to coordinate with the effectors and other modules to avoid conflicts. Also, this may be why humans don’t think like this.

Policy modules can be learned to approximate actions from mode 2 reasoning. This is the process of learning a new skill. In humans, system 2 thinking can be done through system 1 after enough learning. For example, in chess, inexperienced players plan steps explicitly and simulate outcomes. Experienced players can instantly recognize patterns and make optimal moves.

Cost

Cost is the sum of an immutable intrinsic cost and a trainable cost or critic.

\[C(s) = \mathrm{IC}(s) + \mathrm{TC}(s)\]Each of these costs are the sum of different sub-costs generated by submodules. The weights of the sub-cost at each state \(u\) and \(v\) are determined by the configurator. This allows the agent to focus on different goals at different times.

\[\mathrm{IC}(s) = \sum_{i=1}^ku_i\mathrm{IC_i}(s)\\ \mathrm{TC}(s) = \sum_{i=1}^kv_i\mathrm{TC_i}(s)\]The IC being immutable prevents the agent from drifting towards bad behaviors. It constrains the behavior of the agent.

\(\mathrm{TC}\) or the critic is trained to predict future intrinsic cost values. The intrinsic cost only considers the current state. The critic can be trained to predict the future cost so the agent can minimize cost in the future. The short term memory stores triplets of (time, state, intrinsic energy): \((\tau, s_{\tau}, IC(s_{\tau}))\). The critic can be trained to predict the cost of a future state or a discounted sum of future intrinsic costs. For example, the loss function of the critic could be \(\|\|\mathrm{IC}(s_{\tau+\delta}) - \mathrm{TC}(s_{\tau})\|\|^2\). This formulation trains the critic to predict the intrinsic cost of a state \(\delta\) steps in the future. \(\mathrm{IC}(s_{\tau+\delta})\) can be replaced with other targets that can be extracted from the sequence of triplets. However, it cannot depend on the future trainable cost itself.

Configurator

The configurator controls the other components of the system. If these components are implemented as transformers, they can be easily configured by adding tokens. The configurator would inject tokens to steer these components in certain directions. For example, it may influence certain types of actions from the actor, or for perception to focus on certain properties.

The configurator is also responsible for setting the weights of the cost terms. This will allow for the agent to focus on different subgoals at different times. The unanswered question is how the configurator can learn to decompose a complex task into subgoals.

World Model

In JEPA, the purpose of the world model is to predict future representations of the state of the world. There are three main issues

- Diversity of the state sequences the model is able to observe during training

- The world isn’t fully predictable, so the model has to predict multiple plausible state representations following an action

- Predictions must be made at different time scales and abstractions

Self-Supervised Learning / Energy-Based Models

In order to train a world model, Yann LeCun proposes an SSL energy-based model (EBM).

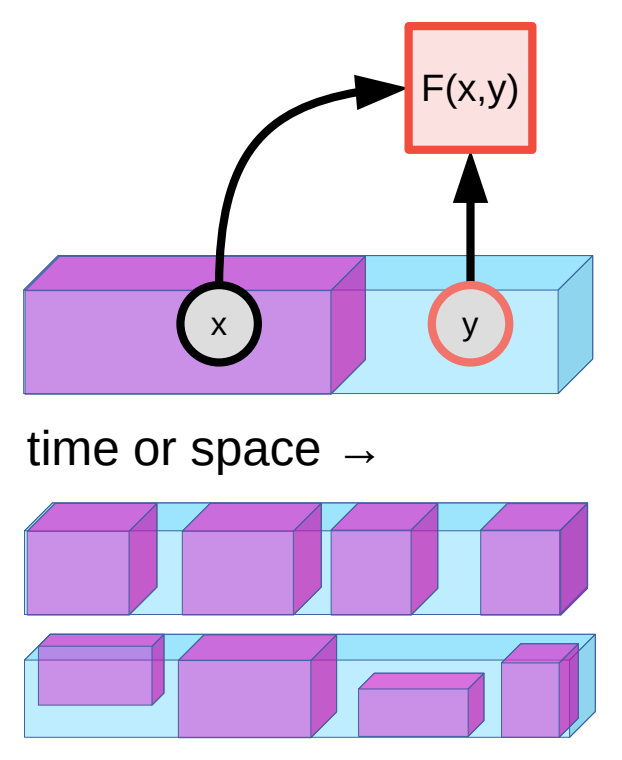

\(x\) and \(y\) can be considered videos, where \(y\) follows x. EBMs learn an energy function \(F(x,y)\) that take low values when \(x\) and \(y\) are compatible and high if not. Compatible in this context means that \(y\) is a plausible continuation of \(x\).

This is different from generative models in that \(y\) is not directly predicted from \(x\). There is a large space of values of \(y\) that can follow \(x\). Predicting exactly what will happen is an intractable problem. However, it is feasible to understand what is possible and what is not. Being good at this task requires an understanding of the world and common sense. A value of \(y\) that defies the laws of physics should result in a high energy value.

However, planning requires predictions of future states. Although \(y\) can’t be predicted directly, we can predict future representations of \(y\). We can get representations from an encoder: \(s_x = g_x(x)\), \(s_y = g_y(y)\)

The encoder will be trained such that the representations are maximally informative about each other, and that \(s_y\) can easily be predicted from \(s_x\). We can make predictions on this representation to enable planning.

A latent variable can be introduced to handle uncertainty. A latent variable is just an arbitrary random variable. It is the source of randomness that is transformed to a useful distribution. Here we want to map the latent variable to the large space of possible values \(s_y\) can take.

A latent-variable EBM (LVEBM) is represented as \(E_w(x, y, z)\).

The energy function can be determined by find the \(z\) value that minimizes the energy. \(F_w(x,y) = \min_{z \in \mathcal{Z} }E_w(x,y,z)\)

The EBM collapses when all pairs have the same low energy. This can happen when the latent variable has too much information capacity. This happens because \(z\) can vary along a larger space. This means that the space for which the energy of \(y\) is low is correspondingly large. If it is too large then the energies of \(y\) collapse. If the \(z\) dimension is the same as the representation dimension, the model can ignore \(y\) entirely and set \(s_y\) to equal \(z\).

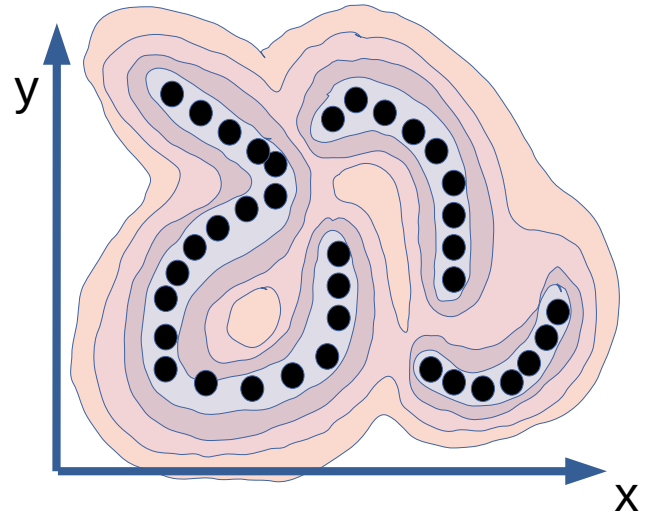

The paper describes a high data density region. This refers to \((x, y)\) pairs that are commonly seen in the real data distribution. We want to lower energy in this region, but keep it high outside of it. Collapse is when the energy is low inside and outside of this region which makes the EBM useless.

There are two training methods used to prevent collapse.

Contrastive methods: Collapse is avoided by increasing the energy with respect to negative examples. It requires some method to generate examples to contrast against. The number of contrastive examples needed grows exponentially with respect to the dimension of the representation.

Regularized methods: In these methods, the loss is regularized to minimize the space in \(y\) where the energies are lowered. These are less likely to be affected by the curse of dimensionality. Contrastive architectures can be regularized. For example, the latent dimension can be constrained.

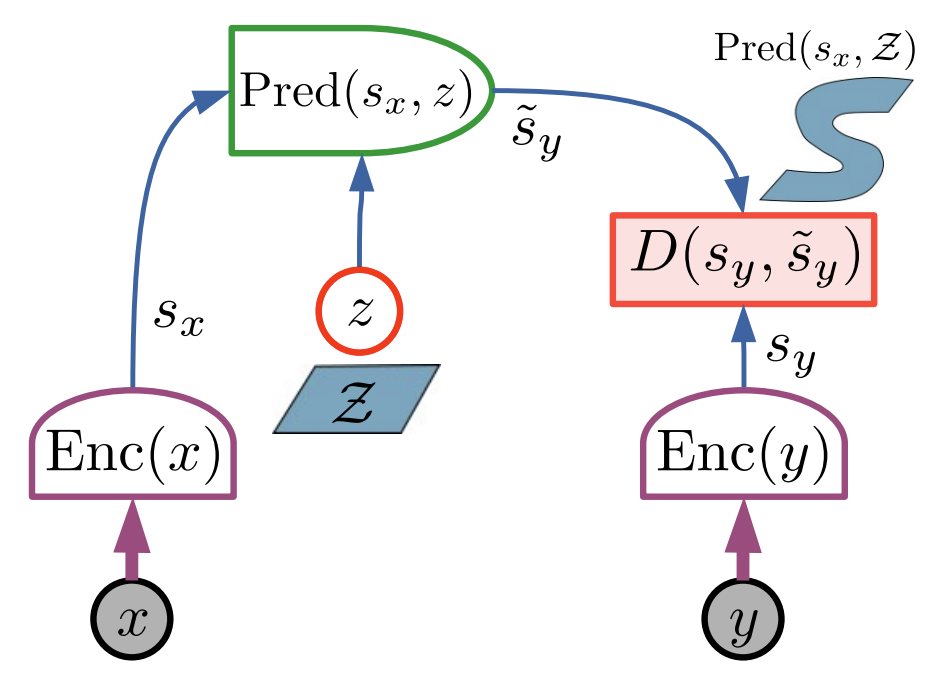

Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture

JEPA is an EBM that performs predictions in the representation space. The energy is the error in predicting \(s_y\) from \(s_x\).

JEPA needs multi-modality, which in this context means to represent multiple possible values of \(y\). There are two ways it can be achieved.

Encoder invariance: This means that \(s_y\) will be the same for different values of \(y\). The encoder ignores aspects of the state that may vary.

Latent variable predictor: Varying \(z\) will lead to different plausible predictions of \(s_y\).

There are four criteria that can be used to train this architecture without contrastive loss:

- Maximize the information content of \(s_x\) about \(x\): \(-I(s_x)\)

- Maximize the information content of \(s_x\) about \(y\): \(-I(s_y)\)

- Make \(s_y\) predictable from \(s_x\): \(D(s_y, \tilde{s_y})\)

- Minimize the information content of the latent variable with a regularizer: \(R(z)\)

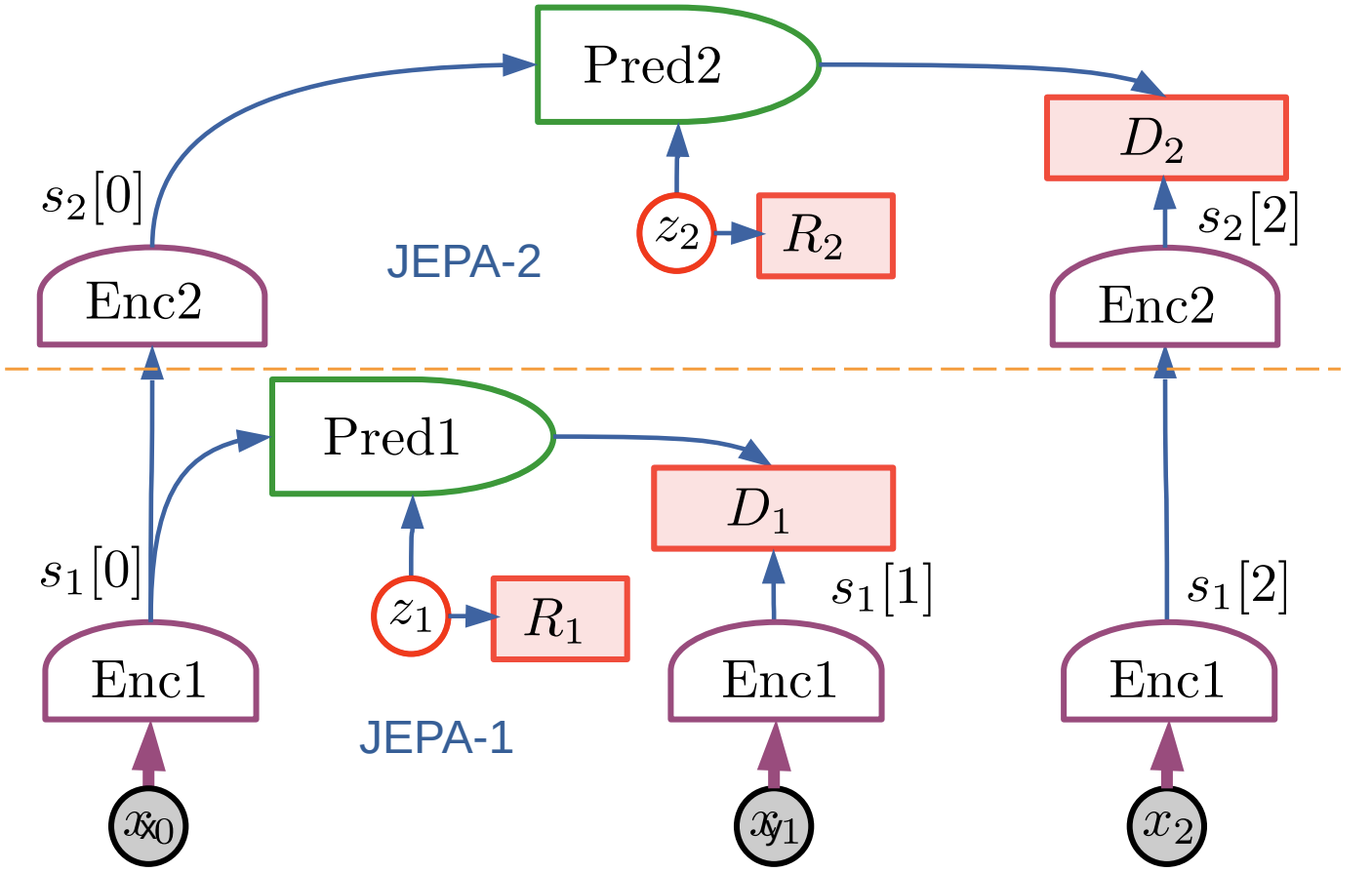

Hierarchical JEPA (H-JEPA)

There is a trade off between information loss in the encoding and the predictability of the encodings. If a representation contains most of the information of the input, it would be hard to predict. A more abstract and higher level representation would be lower in dimension and more predictable. Higher dimension representations are also more suitable for longer term predictions.

H-JEPA (Hierarchical JEPA) enhances JEPA’s abstraction capabilities by splitting the architecture into two parts. The first JEPA handles low-level representations for short-term predictions, while the second operates at a higher abstraction level for longer-term forecasts. This two-tier structure, though innovative, is arbitrary. True intelligence requires multiple levels of abstraction. However, it is not clear how many levels of abstraction are needed. We may even need variable levels of abstraction. Different situations have different levels of complexity.

This architecture can enable higher level planning. In JEPA-2, we can sample from the latent variable for several time steps. Directed search / pruning can be employed in order to efficiently search. This search can be used to determine an optimal action.

This kind of search would be different in JEPA-1 or without H-JEPA because the latent dimension would be too large to efficiently sample from. Abstraction is needed to enable this kind of planning.

World Model Architecture

The world is unpredictable but the agent itself is predictable to the agent. This may motivate a model of self (ego model) that does not have a latent variable.

The state of the world varies only slightly between time steps. Rather than regenerating, it can be updated in memory. With this architecture, the world model will only output the change in the state. This can be implemented with an attention-like mechanism.

- The world model outputs query value pairs: \((q[i], v[i])\)

- The world model retrieves a value from memory using the query

- \[\mathrm{Mem}(q) = \sum_jc_jv_j\]

- The value retrieved from memory is a weighted sum of all values.

- \[\tilde{c}_j = \mathrm{Match}(k_j,q)\]

- Measures dissimilarity between the key and query.

- \[c = \mathrm{Normalize}(\tilde{c})\]

- This is often a softmax.

- \[v_j = \mathrm{Update}(r,v_j,c_j)\]

- Value is updated using the current value and new value.

- The update function can be \(cr+(1-c)v\)

- \[\mathrm{Mem}(q) = \sum_jc_jv_j\]

Data Streams

In building a world model, we have to consider the fundamental differences in the type of data that humans and AI models process. Yann lists 5 modes of information gathering that an agent can use to learn its world model.

- Passive observation: sensor stream without control

- Action foveation: The agent can direct attention within the data stream

- Passive agency: Observing another agent’s actions and causal effects

- Active Egomotion: The sensors can be configured, for example moving a camera

- Active Agency: Sensory streams that are influenced by the agent’s actions

Current AI methods largely focus on passive observation. Other modes may be needed to reach intelligence.

AI is trained on internet data. Internet data is not experienced by the agent. Humans train on data that they experience. This is a fundamental difference. This is also why autonomous cars need so much training data. The AI driving systems don’t have other datasets that they have experienced. For example, if they trained on a large dataset of just walking around, they would need less driving data.

It is challenging to create large-scale datasets from the perspective of an agent, especially reaching the scale of internet datasets. A present-day example is autonomous car datasets. AV companies have large fleets of vehicles on the road collecting data. These are active data streams.

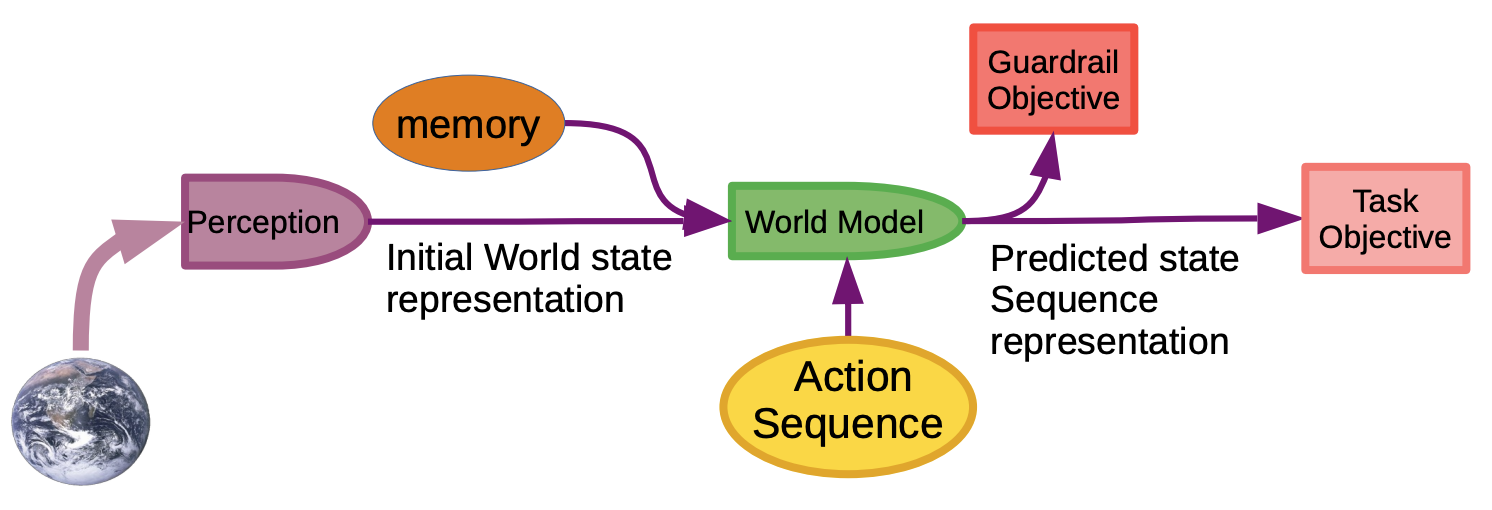

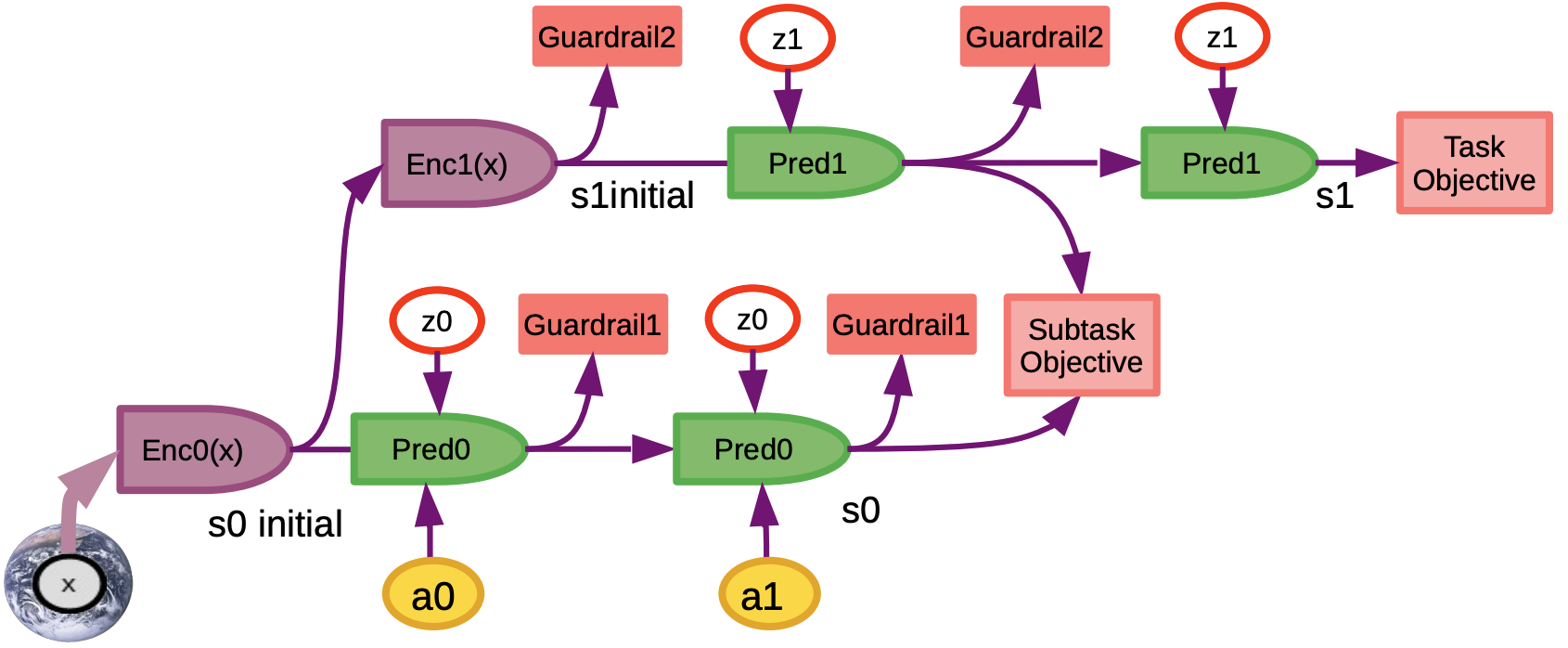

Objective Driven AI

The components of this architecture can be put together to build an intelligent system that follows human defined objectives.

Perception is used to generate an initial representation of the state of the world. The actor proposes a sequence of actions. The world model then predicts the state reached if the action sequence is executed. This state is then used in the objectives. The task objective defines what we want the system to do. This could be a task or particular problem. The guardrail objective makes sure the system accomplishes the task without any unwanted behavior. These guardrails would be designed for safety.

The action sequence is optimized with respect to the objects. There will be a lot of flexibility in designing the objects to get the system to behave in the way we want.

The system can also be extended to achieve hierarchal planning. The higher levels of planning produce a state that will serve as an objective for the lower level. This state can be considered as a subgoal that is necessary to achieve the higher level goal. We can have unique objectives and guardrails for each level of planning.

Latent variables are also introduced to represent the uncertainty in predictions of future states. The latent variables at the higher levels can be thought as imaginary higher level actions. However, only the lower level actions can actually be directly executed.

Towards Implementing JEPA

The JEPA paper is a position paper that describes a vision for AI that may take decades to materialize. However, since its publication in the summer of 2022, there have been a few steps in advancing the architecture. These papers particularly explore the training of JEPAs. They do not explore the other components such as planning. These JEPAs are the first steps to creating a world model.

These are essentially self supervised pretraining methods. When comparing against other works, these papers cite training speed as their advantage. They can achieve strong downstream performance with fewer pretraining epochs.

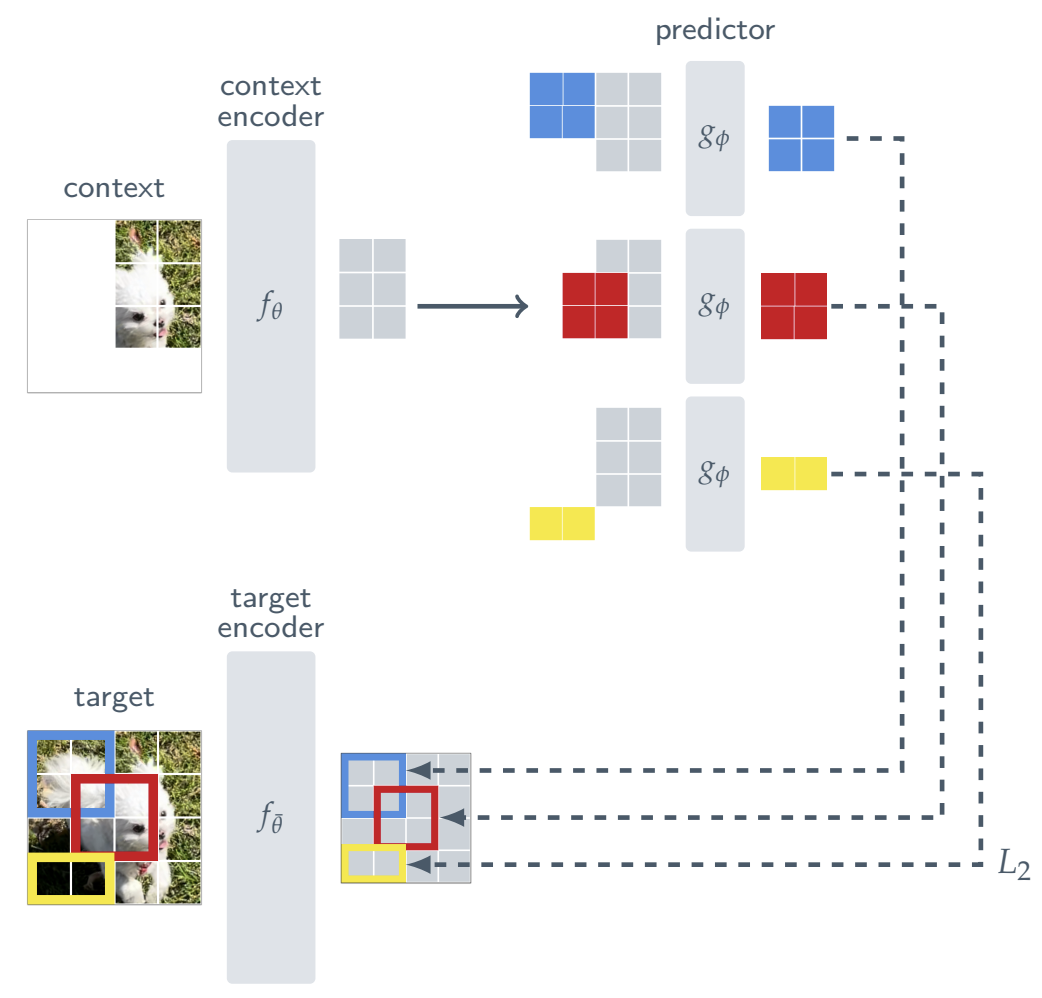

I-JEPA: Self-Supervised Learning from Images with a Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture

Compared to other image SSL approaches, I-JEPA takes advantage of the flexibility of the transformer architecture. ViT is used because it can handle an arbitrary amount of patches in an image, without requiring a strict shape in the input like CNNs

The input image is split into \(N\) non-overlapping patches and fed into a target encoder \(f_{\theta}\) to compute patch representations. \(s_y = \{s_{y1} … s_{yN}\}\)

\(M\) possibly overlapping blocks are sampled from these representations. These blocks are basically larger sections of the image that contain multiple patches.

Context is generated by sampling a block (larger than the target blocks). When predicting a target from this context, the overlap with the target block is masked from the context. The network is trained to predict the representations of the target blocks given the context block, and position encodings for the target block. The position encodings are added to the input so that the model knows where the target is. It is just tasked with predicting representations at those positions.

This architecture avoids collapse by having exponential moving average weights in the target encoder. This is the same approach used in data2vec and BYOL.

The main hyperparameters introduced by this work is the scale and aspect ratio of the target and context blocks. Generally, a small context is used to make this task difficult, which would force the model to learn higher level and more useful features.

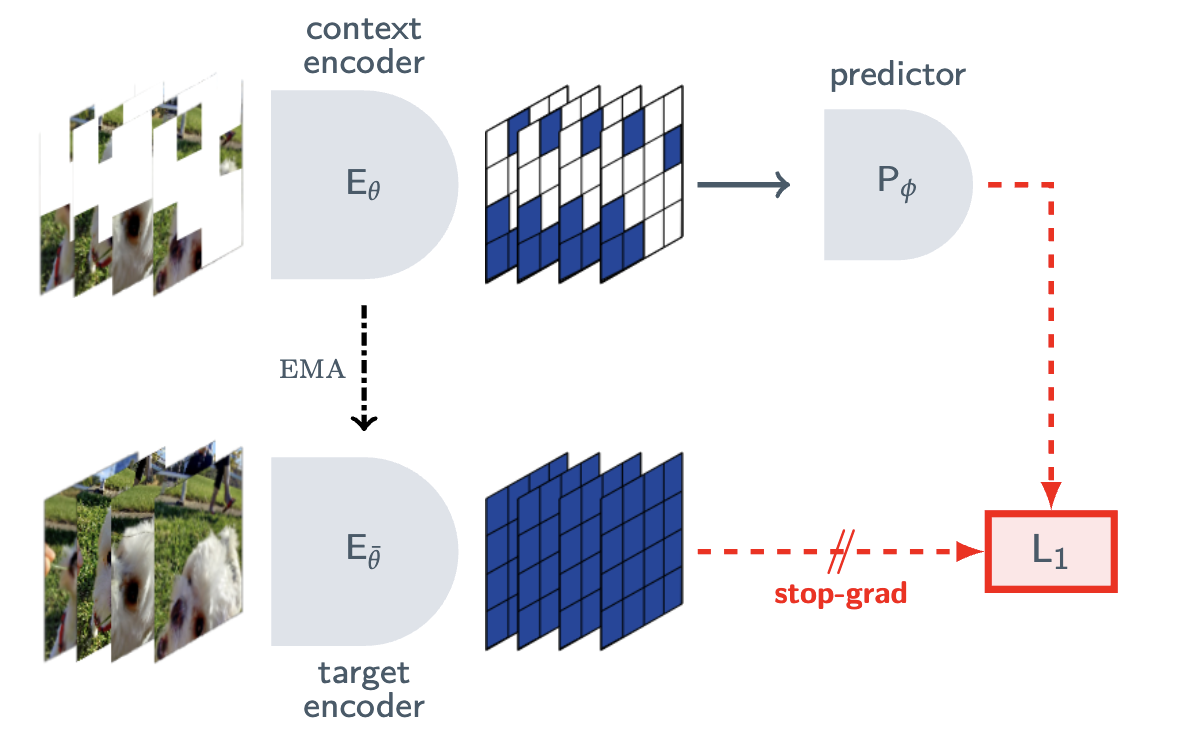

V-JEPA: Revisiting Feature Prediction for Learning Visual Representations from Video

V-JEPA is an extension of I-JEPA to videos. This is done by treating videos are 3d images.

- A clip of 64 frames (~2.1 seconds of video at 30 frames per second) is extracted from the video and resized to 16 × 224 × 224 × 3.

- The clip is split into \(L\) spatiotemporal patches of size 16x16x2 (2 is the number of consecutive frames.

-

A random mask is calculated for the context. This is a 2D that is similar to the mask in I-JEPA. This mask is then repeated across the time dimension. This repetition is necessary because the videos are short and there would be too much redundancy for the same patch at different time steps. This redundancy would make the learning task too easy. This masking creates a context image, while the target is the original image.

- 2 masks are sampled: one short range and one long range. The short range mask covers less area in the image and is more discontinuous. These masks are constructed by different configurations of overlapping blocks, as done in I-JEPA. The target encoder only needs to run once, even if there are multiple masks for the context. Having multiple masks leads to more efficient training.

- The tokens are processed by a transformer encoder (linear projection of patches + multiple transformer blocks). The masked out patches do not need to be processed. There is a separate encoder for the target and context. The target encoder is an EMA of the context encoder (same as I-JEPA).

- The predictor predicts the representations of the masked tokens by the unmasked tokens processed by the context encoder. The loss is the L1 distance between the representations of these masked tokens (from the target encoder, and the context encoder + predictor).

This is predicting gaps in short videos. It does not predict across time. Human learning is across the time dimension.

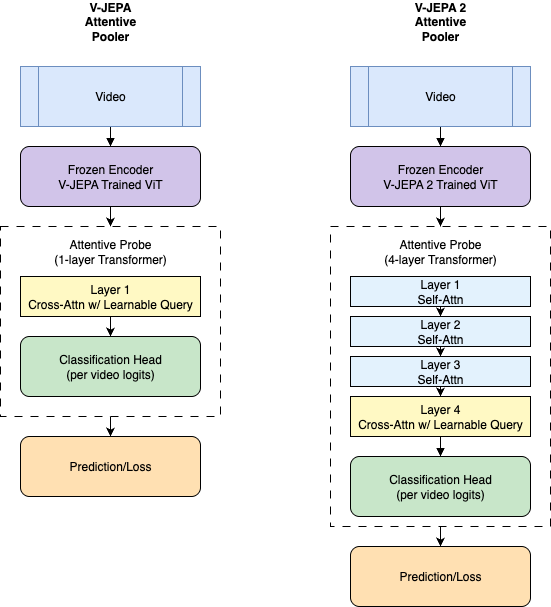

Attentive probing is used to evaluate this model on different finetuning tasks. This is needed in place of linear probing since the input size may vary. This just requires learning a query token specific to the task and a linear classifier on top of the pretrained encoder.

V-JEPA processes small sequences of frames. These short videos are essentially images with a little animation. However, that is the current state of video self-supervised learning. To achieve a model that is closer to human or even animal-level intelligence, this approach needs to scale up significantly. The resolution of the video needs to be increased. Also, the model needs to process longer durations of video and make predictions across time. For example, you should be able to predict what happens in the next 1 minute, based on the previous ten minutes of video input. Such a model could be the basis for an intelligent agent’s world model.

V-JEPA is a very interesting model that may be the start of a highly important line of research.

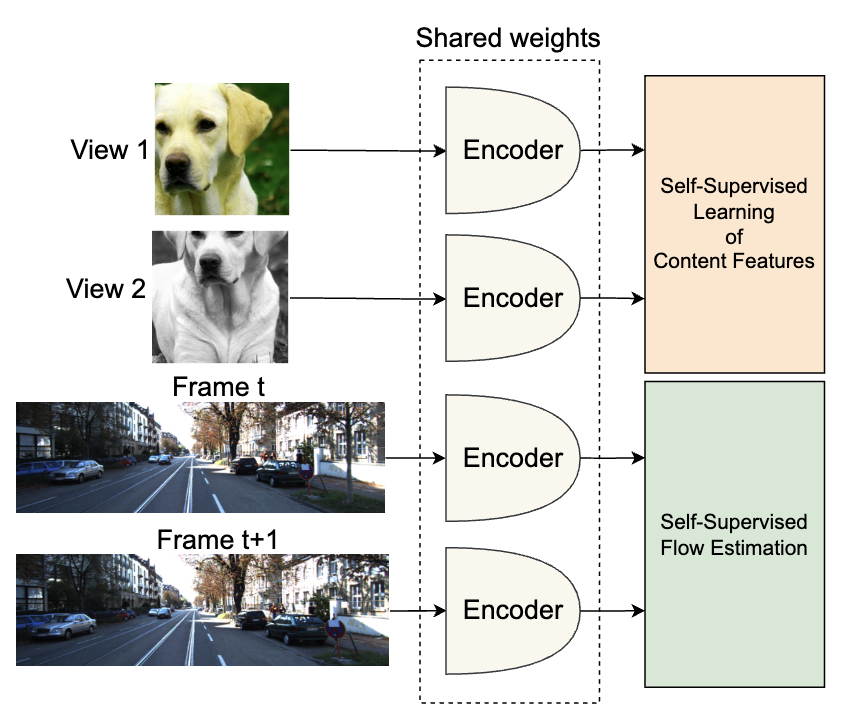

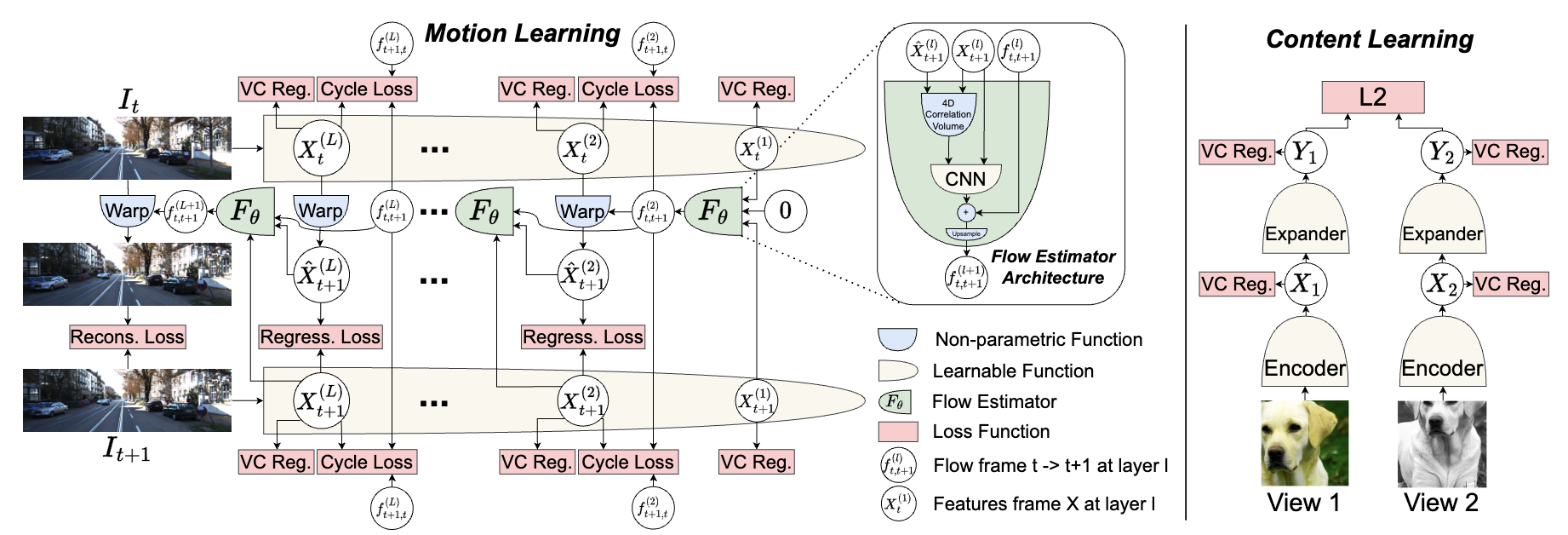

MC-JEPA: A Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture for Self-Supervised Learning of Motion and Content Features

This is an extension of JEPA to include motion information. It uses an optical flow objective to learn motion from videos and uses general SSL to learn about the content of the images/videos. Optical flow is estimating the direction in which pixels move between two consecutive frames of a video.

The details of this dense flow estimation are out of the scope of this blog post. Flow estimation and content feature learning are combined as a multitask learning objective. Images are sampled for content learning, while consecutive frames are sampled from videos for flow estimation. The encoder is shared for both tasks. This is a JEPA architecture because the representations from one frame are warped to match the representations from the next frame. The same encoder is used to process both frames.

The architecture for flow estimation is hierarchal. This may be the first instantiation of an H-JEPA architecture. This architecture is based on PWC-Net. Each level has a different resolution.

The image features are sampled from ImageNet, while a video dataset is used for flow estimation. It is also possible to use frames from video as images for content learning.

This work shows that the JEPA framework is generalizable. There are a lot of ways that we could design a world model and it could include many possible objectives.

What’s Next?

The current research in JEPA represents a significant step towards Yann LeCun’s vision of building a world model capable of human-level AI. While the present focus is on creating effective representation learning models for visual data, the ultimate goal is far more ambitious. The holy grail of this research is a V-JEPA model that can predict across extended time horizons, potentially through a Hierarchical JEPA architecture capable of processing complex, lengthy videos like 10-minute YouTube clips.

To realize this vision, several crucial advancements are necessary. Firstly, we need to embrace true multimodality, incorporating audio and other modalities that are often overlooked in current video models. Scaling up V-JEPA is also essential, requiring larger video datasets and more sophisticated model architectures that can handle higher resolutions. Additionally, the development of more challenging benchmarks for video understanding is critical, as current standards fall short of the complexity seen in image or language modeling tasks.

Future iterations of V-JEPA must evolve beyond spatial masking to make predictions across various time horizons. This capability to forecast future representations based on present information is fundamental to understanding the temporal dynamics of video content. Achieving this may necessitate a hierarchical JEPA structure, where different levels handle predictions at various time scales and abstraction levels. Maybe the next JEPA paper will introduce a hierarchal video JEPA (HV-JEPA).

V-JEPA 2

[2025-07-04 Update]

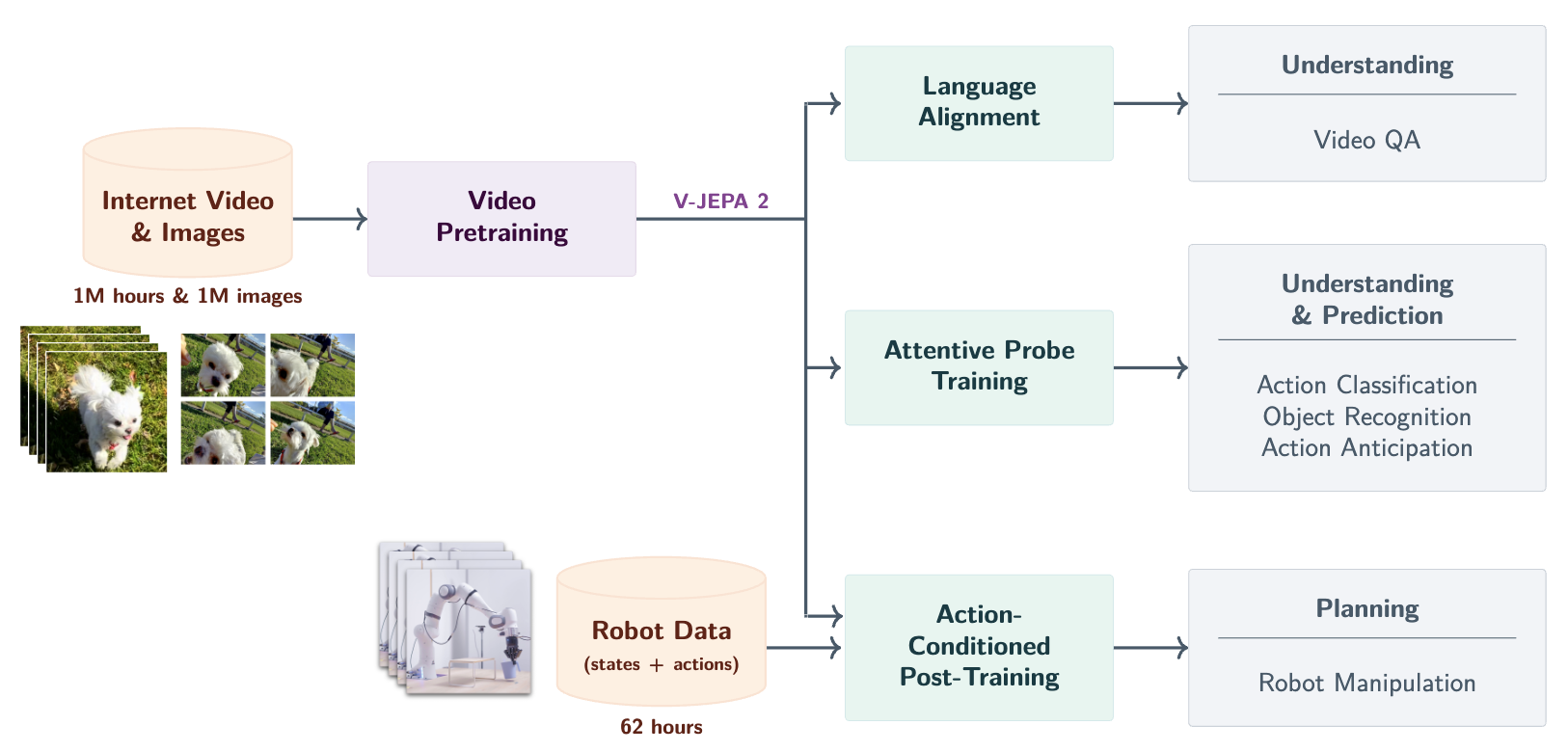

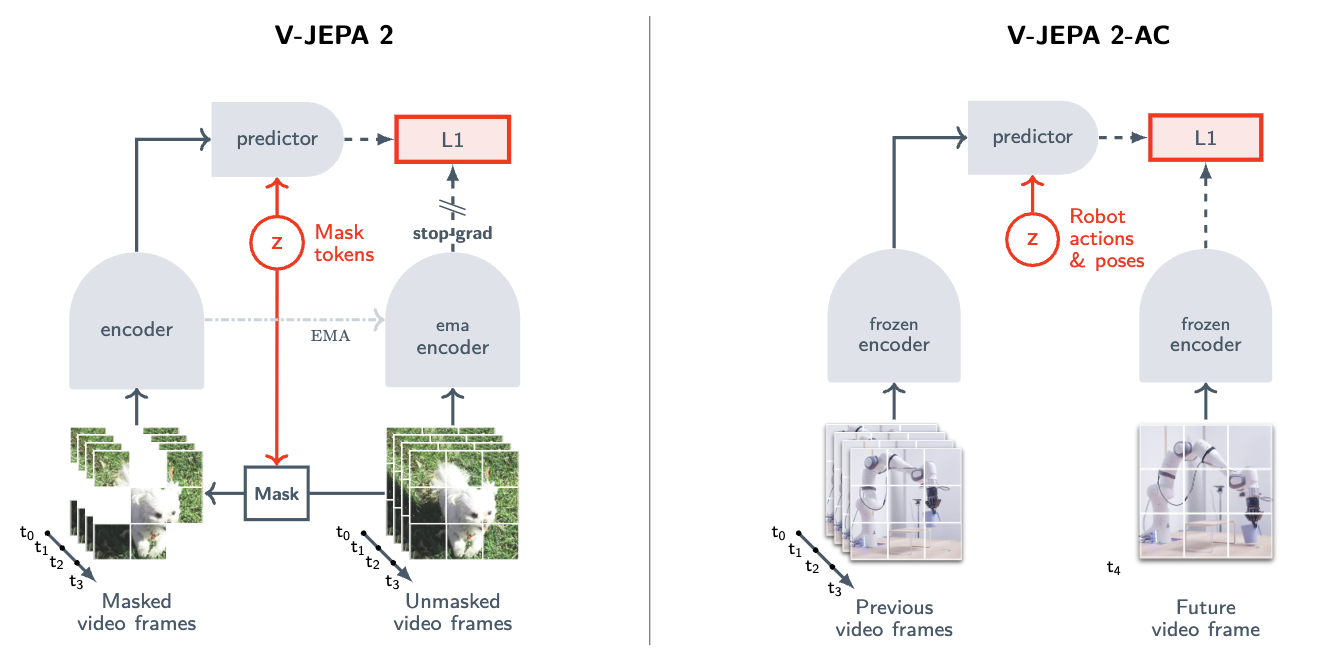

V-JEPA 2 keeps the same model architecture and pretraining method as the original models. However, the model size and the datasets are scaled up. The authors also introduce some interesting post-training methods that unlock more capabilities for this model.

First we will compare the model architectures and datasets, and then delve into the post-training methods.

Model Comparison

| V-JEPA 1 | V-JEPA 2 | notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Backbone | \(\text{ViT-L/16}\), \(\text{ViT-H/16}\), \(\text{ViT-H/16}_{384}\) | \(\text{ViT-L/16}\), \(\text{ViT-H/16}\), \(\text{ViT-g/16}\) | 16 is the patch size. The models use a standard resolution of 224x224 images. \(\text{ViT-H/16}_{384}\) uses a larger resolution of 384x384. |

| Largest Model Size | \(\text{ViT-H/16}\) (630M Params) | \(\text{ViT-g/16}\) (1B Params) | |

| Pretraining Dataset | VideoMix2M (2 million videos) = Something-Something v2 (168K videos, 168 hours) + Kinetics-400/600/700 (733K videos, 614 hours) + Howto100M (1.1 M videos 134K hours) | VideoMix22M (22 million videos) = VideoMix2M + YT-Temporal-1B (19 M videos, 16M hours) + ImageNet (1M images) | Both datasets are combinations of existing video and image datasets. Weighted sampling and data curation are used during training. |

| Model Input | ~3 seconds of video (16 frames, 4 FPS) | ~16 seconds (64 frames, 4 FPS) Progressive-Resolution training is used. Higher frame counts were tested but were not more effective. | |

| Finetuning | Finetuned on motion classification on SSv2 and action recognition in K400. Attentive probing is used to evaluate on image and video tasks. | Various post-training methods used: language alignment for visual question answering, attentive probing for action and object recognition, and action-conditioned post-training for robot manipulation |

Post Training

We have seen the transformer architecture, which started with language, take over many other modalities. A more recent trend is that LLM training methods and recipes (pretraining → SFT → RL) are being adapted to other domains. V-JEPA 2 represents another iteration of this trend. We will explore the different types of post-training implemented in V-JEPA 2.

Progressive-Resolution Training

We also see a form of long context finetuning in the progressive-resolution training. This is part of the video pretraining recipe. While most pretraining is done with 16 frames, the model is then further trained on 64 frames during the cooldown phase. This enables efficiently training a model that can process longer video clips. This is the same way that LLMs are trained to process long contexts.

Attentive Probe Finetuning

This method was implemented in V-JEPA 1. A larger attentive probe is used in comparison to the evals in V-JEPA 1.

This attentive probe finetuning leads to strong performance on action classification and object recognition evals.

V-JEPA 2 introduces an evaluation on action anticipation. The Epic-Kitchens-100 human-action anticipation task evaluates the model’s ability to predict future actions. This is represented with an action, verb, and noun. This can be considered as 3 classification tasks. An attentive probe with three learnable query embeddings is used for this. The eval task is structured so that the model predicts what action is taken 1 second into the future. This is limited in that it can only predict from a fixed set of actions, verbs, and nouns. It also can’t predict multiple actions or on a longer time frame.

LLM Conditioning

V-JEPA 2 is used as a video encoder for an LLM. This enables evaluation on Video Question Answering.

This uses the architecture and visual instruction tuning training method of LLaVA models. The JEPA embeddings are projected into the input of the LLM as non-tokenized early fusion. The visual instruction tuning method from LLaVA is used to train this architecture.

- Only the projector is unfrozen and trained on image captioning

- The model is trained end to end on image question answering

- The model is trained end to end on video question answering

Action Conditioned Post-Training

The model is also evaluated for robotics. It is post-trained on 62 hours of video from the Droid dataset. This model is then deployed on Franka arms. This is a tabletop arm with a fixed camera. The actions are end-effector commands. There are 7 degrees of freedom so that effector states can be represented by the 7D vector. The actions are changes in these states. These diffs are used to form commands.

The V-JEPA 2 encoder \(E(\cdot)\) encodes each of the 16 frames into a feature map. We get 16 feature maps \((z_k)_{k \in [16]}\), where \(z_k := E(x_k) \in \mathbb{R}^{H \times W \times D}\). With 16×16 patches, we get an output of size 16×16×1408. The feature maps are interleaved with the actions and states: \((a_k,s_k,z_k)_{k \in [15]}\). Note that we have 15 of these tuples since the actions are formed by the differences between states.

This is processed by the predictor model \(P_{\phi}(\cdot)\), which is a separate 300M parameter autoregressive transformer. Given the action, state, and previous feature maps, it predicts the next feature map. The result is a sequence of predicted feature maps \((\hat{z}_{k+1})_{k \in [15]}\).

We can then apply a teacher forcing loss, similar to next token prediction SFT in LLMs. Note that \(k=0\) is skipped because there is no prediction at the first timestamp.

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L}_{\text{teacher-forcing}}(\phi) &:= \frac{1}{T}\sum_{k=1}^T \|\hat{z}_{k+1} - z_{k+1}\|_1\\ &= \frac{1}{T}\sum_{k=1}^T \|P_{\phi}\left( (a_t, s_t, E(x_t))_{t<k} \right) - E(x_{k+1})\|_1\end{align*}\]A two-step rollout loss (\(T=2\)) is also used. We start with the initial state and feature map, then use the first \(T\) actions to rollout to the \(T+1\) feature map. We then minimize the distance between the true \(T+1\) feature map and the one predicted by the rollout. This differs from the teacher forcing loss since we only have the true state and feature map for the initial state. The subsequent states and feature maps are predicted by the model.

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{rollout}}(\phi) := \|P_{\phi}(a_{1:T}, s_1, z_1) - z_{T+1}\|_1\]We train on a combination of the teacher forcing and rollout loss.

\[L(\phi) := \mathcal{L}_{\text{teacher-forcing}}(\phi) + \mathcal{L}_{\text{rollout}}(\phi)\]During this training the V-JEPA 2 encoder is frozen. We train the predictor network to enable planning.

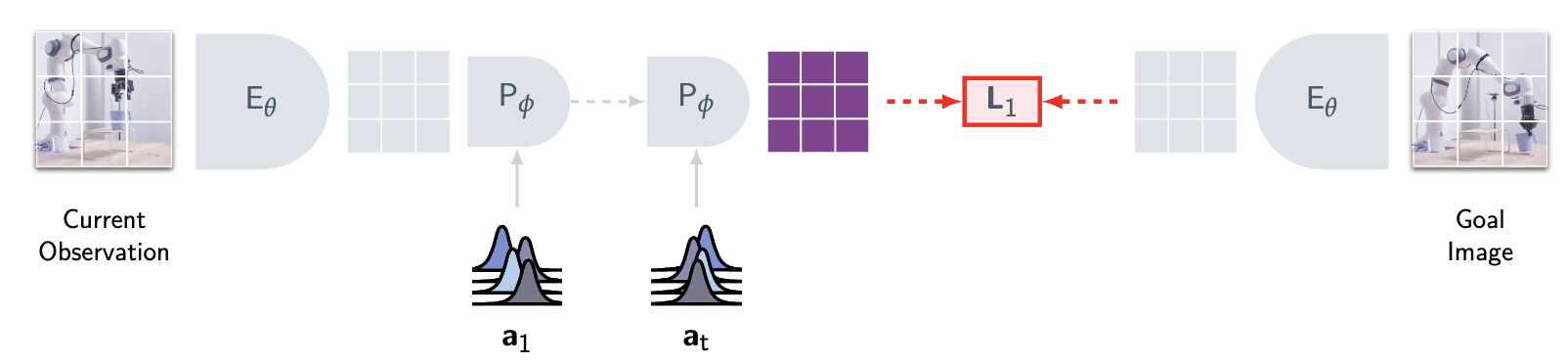

For planning we use the Cross Entropy Method (explained in my World Models blog). This method is used to minimize the goal conditioned energy function at inference time:

\[\mathcal{E}(\hat{a}_{1:T}; z_k, s_k, z_g) := \|P(\hat{a}_{1:T}; s_k, z_k) - z_g\|_1\]\(z_g\) represents the feature map of the goal state. This uses the same method as DINO-WM (World Models blog). We get an action sequence \((a_i^\star)_{i \in [T]}\) through this optimization.

An interesting future direction is to use this world model for language-specified goals. We can train an LLM to generate the goal latent embedding from text. Here is a simple design for implementation:

- Collect a robotics dataset containing pairs of (action, video), where actions are free-form text and videos are short clips of robots performing these actions.

- Initialize an MLLM with a JEPA video encoder and a predictor network.

- Use the action-conditioned training method to train the predictor and the MLLM.

- The loss functions would need adaptation:

- Add a loss term that forces the MLLM-generated embeddings to be close to the representation of the final image.

- Include the MLLM embedding as an input to the predictor. Backpropagate gradients to both the LLM and the predictor.

- The loss functions would need adaptation:

V-JEPA 2 proves to be an effective world model when applied to robotics planning. This robotics application brings JEPA closer to the brain framework introduced in the original JEPA position paper, demonstrating how to build a JEPA world model and use it for real-world planning.

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Bandaru, Rohit (Jul 2024). Deep Dive into Yann LeCun’s JEPA. https://rohitbandaru.github.io.

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{bandaru2024deep-dive-into-yann-lecun-s-jepa,

title = {Deep Dive into Yann LeCun’s JEPA},

author = {Bandaru, Rohit},

year = {2024},

month = {Jul},

url = {https://rohitbandaru.github.io/blog/JEPA-Deep-Dive/}

}