Self-Supervision from Videos

In a previous blog post, we explored image-based self-supervised learning primarily with contrastive learning. Self-supervised learning offers a way to train an ML model to generate useful image representations using large amounts of unlabeled data. The resulting models can be used for a wide variety of downstream tasks, such as classification, object detection, or segmentation on different datasets.

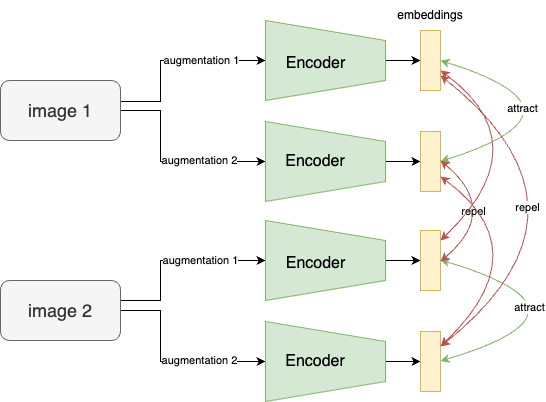

Many of the current state-of-the-art results come from contrastive self-supervised learning. In contrastive SSL, an image from the dataset is transformed using multiple data augmentations, including cropping, color distortion, and flipping. These augmentations are inputted into a neural network to get representations. A contrastive loss is applied to push representations from the same image (different augmentations) closer together, and representations from different images are pushed further apart. Training with this objective will learn image representations that encode the content of the image. The data augmentations are needed for the network to avoid trivial solutions to optimize the contrastive loss, which would be comparing pixel values instead of the image’s semantic content.

Contrastive learning is limited by its dependence on data augmentations. These augmentations are hacky and unnatural. They can change the meaning of the image. The act of augmenting an image destroys some amount of information.

Example from Purushwalkam et al showing that cropping can remove semantic information in images.

Many AI researchers believe that humans learn through self-supervised learning. However, humans most likely don’t learn with data augmentations. It is unlikely we mentally do crops and color distortions. It is more likely we learn by tracking objects through time. For example, if you are watching a dog, the dog looks different from one point in time to another. The dog is likely in a different pose, different location, and has different lighting conditions. Through time, we can get natural data augmentations, but can they help train better image representation models?

The blog post explores whether video can improve self supervised computer vision models. We look at some papers with different approaches to the problem.

Image vs Video Representations

Image and video representations are two distinct research problems. Image representation learning aims to learn fixed-size embeddings of images, while video representation learning aims to learn fixed-size embeddings of videos. There are many papers on applying contrastive learning techniques to videos; however, these involve applying data augmentations to videos. In this post, we will also discuss using videos to learn image representations so that we can utilize the concept of obtaining natural data augmentations from videos.

Learning Video Representations

Video representation learning can be understood through its downstream tasks. One of the most common datasets is Kinetics. Which consists of short clips of human actions which are to be classified into classes such as “saluting” and “cutting cake”.

Spatiotemporal Contrastive Video Representation Learning

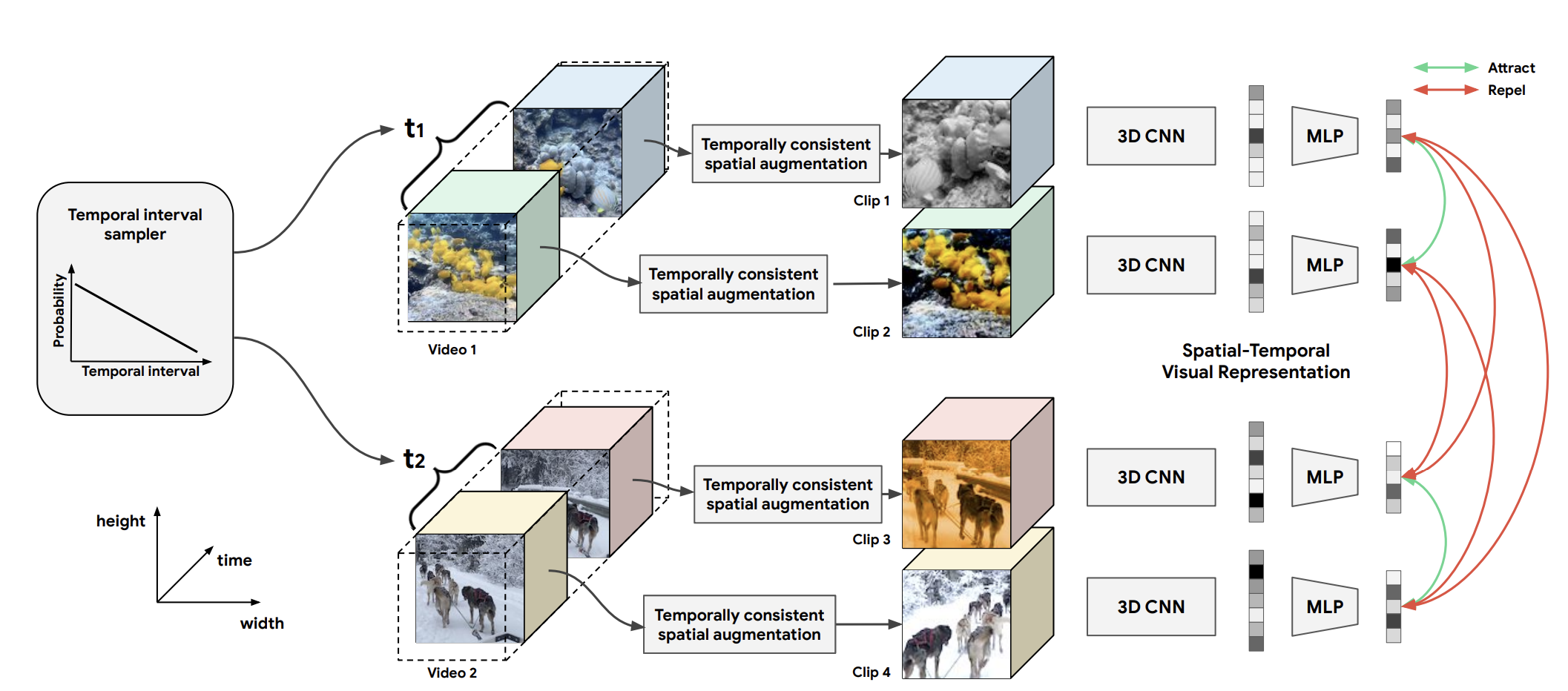

This work is very similar to SimCLR. It uses contrastive learning to learn representations of videos. Like SimCLR, InfoNCE loss is used to bring closer the representations of positive pairs and repel those of negative pairs. Positive pairs are data augmentations of the same video. There are two main differences with SimCLR:

1) 3D CNN model architecture for the video encoder to produce representations

3D-ResNets are used instead of 2D-ResNets.

This is a natural extension of CNNs to handle video that treats time as a third dimension. This architecture obtains a fixed-size representation from a fixed number of frames of a certain resolution.

2) Spatiotemporal data augmentations

In addition to the standard image data augmentations used in other contrastive SSL methods (color jittering, cropping, etc.), the authors add spatial and temporal augmentations. These are designed specifically for videos. It is important to carefully design the data augmentations used for videos. If the augmentations are too aggressive, the representations will be invariant to useful information. If the augmentations are too weak, the representations may learn trivial solutions.

Temporal Augmentations

The temporal interval is sampled first. This interval is the time difference between the two augmentations. Smaller intervals have more probability, which is desired because temporally distant augmentations might be too far apart. We want the content of the two augmentations to be the same. The further apart in the video they are, the less likely this is.

Spatial Augmentations

Applying spatial augmentations to each frame independently has the disadvantage of destroying motion between frames. If each frame is randomly cropped, the objects will randomly move around frame to frame. We want to preserve the consistency between frames. The solution to this is to sample a frame-level augmentation once per video clip and apply the same transformation to each frame. If each frame is cropped to exactly the same pixels, the motion will be perfectly preserved. For contrastive learning, we use data augmentations to make negative examples more different. We want two video clips to be different, but there is no need to make the frames of a single clip different from each other.

This paper is a great example of how image SSL techniques can be extended to videos. It just requires different model architectures and data sampling / augmentation techniques. There are some gaps to this approach:

- It can only produce representations for fixed-size video clips. The resulting model can’t be used for downstream image tasks.

- Temporal data augmentations can still destroy some temporal information in the video, especially fine-grained details.

- Spatial data augmentations such as cropping are required and can be used to learn unwanted spatial invariances.

Learning Image Representations from Video

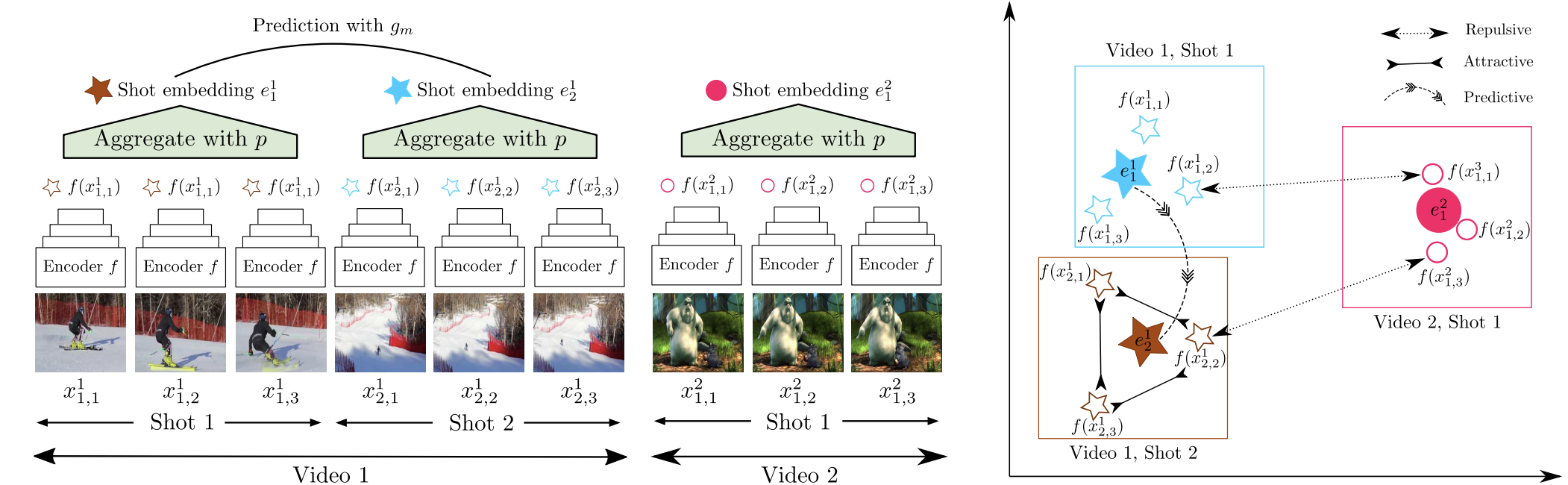

Self-Supervised Learning of Video-Induced Visual Invariances (VIVI)

They developed a video-based self-supervised learning framework for image representations and evaluated it on the VTAB image representation benchmark.

This uses the YouTube 8M dataset. This is a larger dataset than Kinetics and contains longer and more complex videos. Videos are composed of frames. In this work, they also utilize “shots,” which are sequences of continuous frames within a video. Shots have a high-level relationship with each other. Frames within the same shot are used as positive pairs, and shots from different shots are used as negative pairs.

Shot embeddings are defined as pooled (mean pooled or attention pooled) frame embeddings. These are used for shot order prediction. An LSTM or MLP is used to predict the next shot embedding given the current shot embedding. This models the relationship between shots in a video. An alternative to shot embedding prediction, would be to contrast shot embeddings between videos.

This paper uses co-training with the ImageNet supervised classification task. There is a long way to go since YouTube-8M is much larger than ImageNet, so ImageNet should not be needed for good results. This gap may be due to the data itself. ImageNet is a relatively clean dataset where the object in each image is usually centered. Video frames from YouTube are much noisier.

Demystifying Contrastive Self-Supervised Learning: Invariances, Augmentations and Dataset Biases

In this paper, the authors observe that the cropping required for contrastive SSL hurts performance on downstream tasks such as object detection. They make a distinction between scene-centric and object-centric datasets. ImageNet is object-centric, which means that a single object is presented in the image and it is centered. The data in video often contains multiple objects in different parts of the frame. For certain tasks, ImageNet is a far superior training dataset due to this bias.

They pretrain and evaluate an SSL model (MOCOv2) with the MSCOCO dataset (scene-centric) and MSCOCO bounding box cropped dataset (object-centric). The results show the effect of cropping when pretraining. They find that object-centric pretraining leads to better object-centric evaluation, while scene-centric pretraining leads to better scene-centric evaluation.

This shows that for scene-centric evaluation tasks like object detection, cropping while pretraining is harmful.

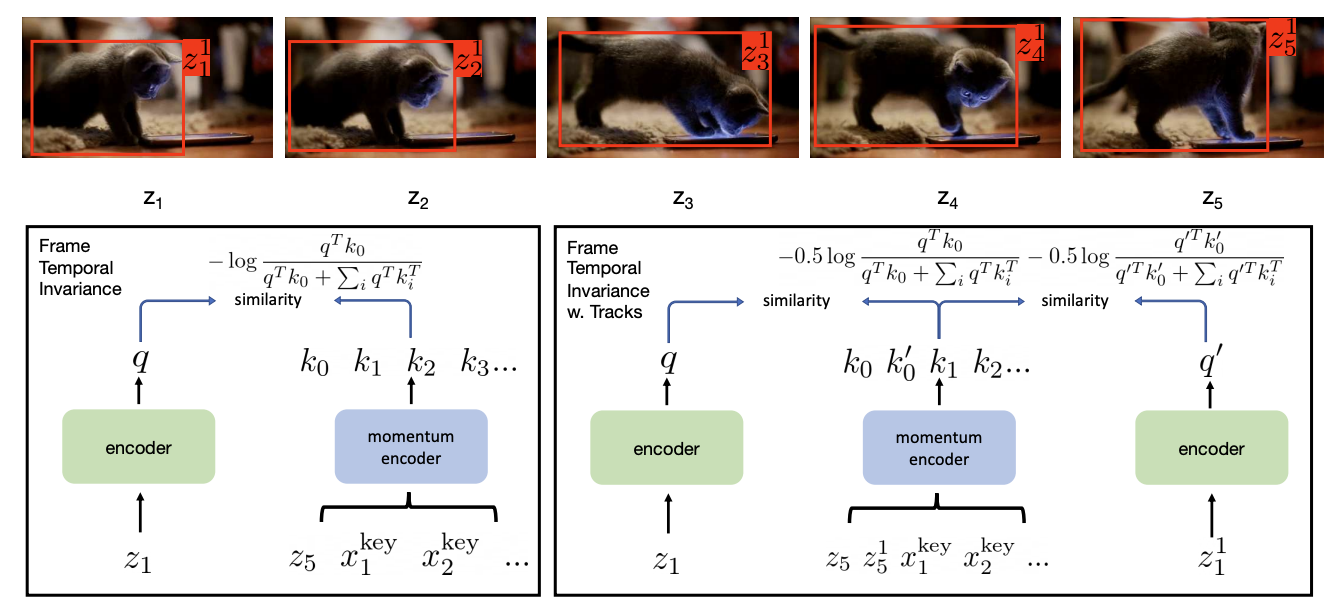

To replace cropping, videos can be used to get “temporal transformations”.

\[\mathcal{V}_{pairs} = \{(z_i, z_{i+k})\ |\ z \in \mathcal{V}, i \in \textnormal{N}(z), i \bmod k = 0\}\]Pairs are formed by frames consecutive frames subsampled by $k$. We do not want frames that are too similar too each other in time, as their difference would be too insignificant. $k$ can be set depending on the frame rate of the video. If it is equal to 60, every 60th frame is considered and adjacent frames are pairs.

\[\mathcal{D}^+ = \{(t_i(z_i), t_j(z_{i+k}))\ |\ t_i,\ t_j \in T, (z_i, z_{i+\Delta}) \in V_{pairs}\}\]The dataset is then formed by applying transformations to the pairs of frames. For this work, the same transformations as MOCO are used. MOCO doesn’t require negative examples to train. Positive example pairs are formed by applying a transformation on the pairs of frames. Although this work explores using video for natural transformations, it still relies on the traditional data augmentations used in SSL.

This contrastive learning setup uses the whole frame, but the authors want to train on object-centric data to make the representations more robust for object recognition.

They use region tracking to make the frames of the video object-centric. They track the same object across multiple frames and use these cropped versions of the frames. This way, the model learns how objects change in a video while ignoring the scene-wide changes. For example, the position of an object in a scene is ignored.

VideoMAE

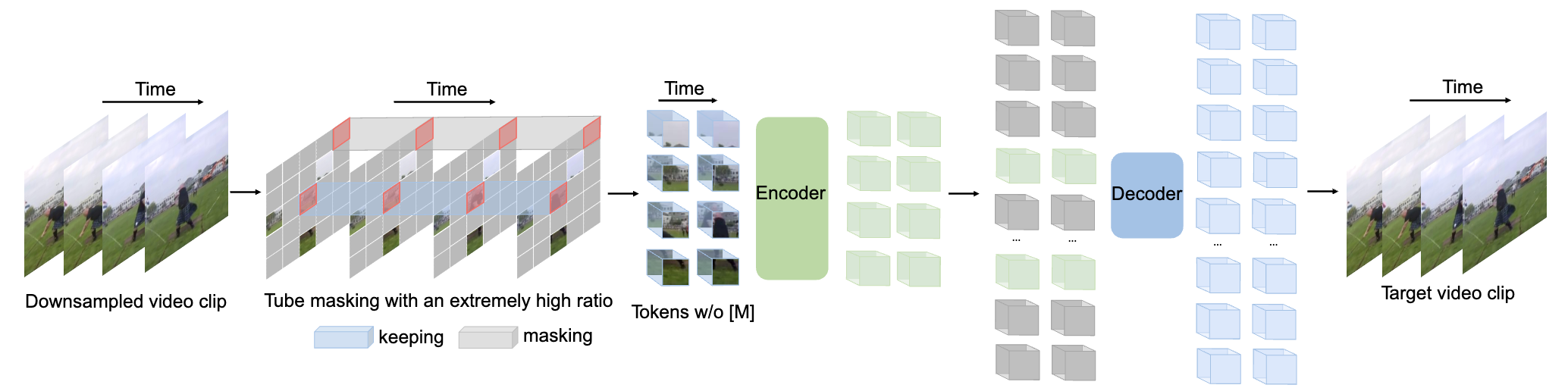

This work extends the MAE work (SSL with Vision Transformers blog post) to video. Rather than using contrastive learning, masked patches are predicted in the video.

The video is represented as a 3D image. The video is split into cubes (in this paper, it’s size 2 × 16 × 16). These cubes are treated like patches in ViT, but with an added time dimension. Each cube in the video is linearly projected and treated as a token embedding in the transformer. A position embedding is also added to the cube embedding. These cubes are treated as tokens in the transformer.

For each video, a tube mask is applied. This means the same patch in multiple consecutive frames of the video is masked. This is meant to make the SSL task harder, as patches don’t change much frame to frame. There is a high temporal correlation that needs to be broken in designing the objective. A high masking ratio, along with the tube masking strategy, ensures the SSL task is difficult and forces the model to learn higher-level spatiotemporal information.

An encoder processes the unmasked tokens. With a high masking ratio, we can save on computation cost by only processing the unmasked tokens. This is feasible with the transformer architecture, but not with CNNs. The encoder maps the token embeddings to a latent space. The decoder then predicts the masked cubes of the video. This can be trained with a simple reconstruction loss like MSE (mean squared error).

One interesting architecture decision is that “joint space-time attention” is just full self-attention. This means the attention captures all pairwise interactions between all tokens. It would be interesting to introduce causal attention on the time dimension. This would mean that within a frame, there is full attention. But cubes can only attend to cubes in the future. However, this type of causal masking would likely require a lower cube masking ratio to be effective.

Many other video SSL methods utilize image data in addition to video data. However, VideoMAE is able to achieve SOTA results on Kinetics-400 (video classification) without this external data. Ideally, we want video SSL methods that do not need to rely on images at all. This paper does not report results on image evaluation tasks. But this architecture would support this. We want video-pretrained models to achieve superior performance to image models on both video and image evaluation tasks. However, current video pretraining methods lag behind image-pretrained methods.

This work leverages the flexibility of the transformer architecture to directly predict elements of the video. This is simpler in that it does not require tracking objects, constructing triplets, or applying data augmentations. It is closer to how language models are trained. This also allows producing image representations and video representations, unlike the CNN methods. This is because the number of input frames to the transformer is variable.

Conclusion

Video lags behind images in representation learning for several reasons. While videos contain more information than static images, this information is spread across a much larger volume of data, making it computationally inefficient to process. The first frame of a video provides substantial information. You can learn what objects are present in the scene and the setting of the video. Subsequent frames offer diminishing returns. Future frames might just have one object moving across the frame. Because of this temporal redundancy, images are more information-dense than videos. Language models are more advanced than image models because language is a significantly more information-dense modality. Videos are an additional order of magnitude less information-dense than images. Data quality also plays a role. Video datasets, though vast, often lack the curated quality of image datasets like ImageNet, impacting the performance of video-based models. These challenges make it harder to build effective models with only video.

Looking ahead, progress in video-based AI will be driven by improved datasets, advancements in computational power, and novel modeling techniques. As these developments unfold, we can expect more sophisticated vision models that effectively incorporate video data, bridging the current gap between image and video understanding in AI systems. This may unlock new capabilities in computer vision models.

Datasets

ImageNet: 1,000,000 images, 1000 classes

Kinetics 700: 650,000 videos, 700 classes, ~10 seconds each, 1800 hours

YouTube 8M: ∼8 million videos, 500K hours of video—annotated with a vocabulary of 4800 entities

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Bandaru, Rohit (Oct 2024). Self-Supervision from Videos. https://rohitbandaru.github.io.

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{bandaru2024self-supervision-from-videos,

title = {Self-Supervision from Videos},

author = {Bandaru, Rohit},

year = {2024},

month = {Oct},

url = {https://rohitbandaru.github.io/blog/Self-Supervision-from-Videos/}

}