Variational Autoencoders: VAE to VQ-VAE / dVAE

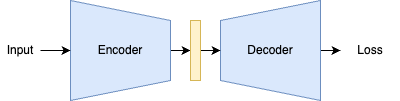

The autoencoder is a simple and intuitive machine learning architecture. It takes a high-dimensional input, uses an encoder to transform it into a lower-dimensional embedding, and then employs a decoder to learn the reverse transformation. The entire model is trained end-to-end with a reconstruction loss, such as mean squared error. We’ll refer to this as a vanilla autoencoder.

The vanilla autoencoder excels at compression and representation learning but faces challenges when used as a generative model. Due to the curse of dimensionality, we can’t effectively sample from the latent space of a vanilla autoencoder. The space of all possible latent representations is vast, with only a small portion occurring in the dataset. Consequently, most random points in this space would decode into noise.

While it might be possible to sample from a low-dimensional latent space, if the dimension is too small, the model loses expressiveness and doesn’t scale well. This type of autoencoder is valuable for representation learning but falls short as an effective generative model. Variational autoencoders seek to address this.

For the vanilla autoencoder, the loss is defined as \(L_{reconstruction}(x, g(f(x)))\). Where \(x\) is the input, \(f\) is the encoder, and \(g\) is the decoder. \(L\) is a reconstruction loss that is often set to mean squared error (MSE). The latent embedding can be represented as \(z = f(x)\). All autoencoders map observed data to latent embeddings where the latent dimension is a hyperparameter.

This architecture is simple to implement and is useful for compression and representation learning. Variational autoencoders were introduced to address different deficiencies of this architecture, which we will cover.

Variational Autoencoders (VAE)

The goal of variational autoencoders is to constrain the latent space of an autoencoder so that it can be sampled from. VAEs use variational inference to create a probabilistic latent space. VAE was introduced in Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes in 2013. Although the acronym VAE isn’t present in this paper.

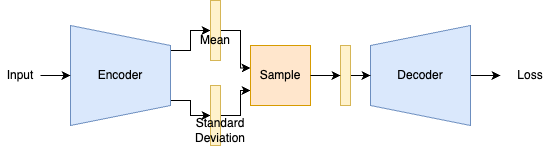

A simple way to construct this would be to have the encoder output the parameters to a Gaussian distribution. A mean and standard deviation are predicted for each latent dimension. Using these parameters, we can sample from the distribution as such.

Reparameterization Trick

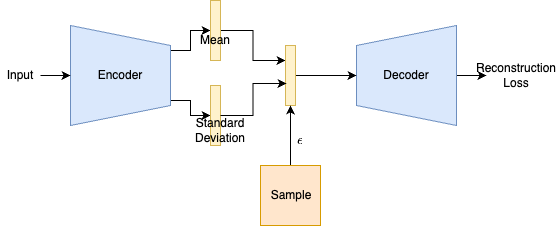

However, the architecture defined above is not trainable. The sample operation is not differentiable, so it would not be possible to train the encoder. A “reparameterization trick” is used to solve this.

\[z=\mu+\sigma\epsilon\]This trick is a simple and clever implementation detail, since Gaussians are normally sampled in this way. We are sampling \(\epsilon\) and then treating the sampling of \(z\) as a deterministic process. This can be done only because \(\epsilon\) is independent of any parameters. The stochastic component is refactored to be a fixed distribution that has no dependencies for backpropagation.

Although Gaussians are commonly used, any distribution that can be reparameterized like this, can be used in a VAE.

Forward Pass

In order to understand how the VAE is trained, we need to introduce some mathematical notation.

Encoder network \(q(z\mid x)\): For each input \(x_i\), this outputs vectors for mean \(\mu_i\) and log variance \(logvar_i\). These parameters are used to generate a latent embedding.

Latent variable \(z\): This is computed using the reparameterization trick. \(z_i = μ_i + σ_i * ε\), where \(σ_i = \sqrt{\exp(logvar_i)}\) and \(ε ∼ N(0, I)\)

Decoder network \(p(x\mid z)\): Given the latent embedding this outputs the parameters of the output distribution. This distribution can be a Gaussian distribution for continuous data (like natural images) or a Bernoulli distribution for binary data.

This notation describes the forward pass of the VAE. We will now explain how this is trained.

Loss

During training, we sample from the conditional distribution\(q(z\mid x)\). At test time, however, we need to use the decoder to generate new samples by sampling from the prior \(p(z)\). For this to work, the model’s marginal posterior \(q(z)\) must approximate a standard Gaussian prior \(p(z) = N(0, I)\). To achieve this while sampling from \(q(z\mid x)\), we add a KL divergence term to the loss function: \(\text{KL}(q(z\mid x) \mid\mid p(z))\). We use the reverse KL divergence specifically to ensure the approximate posterior places probability mass only where the prior does. This KL term has a closed form for Gaussian distributions:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal{L}_{KL}(x,z) &= \text{KL}(q(z\mid x) \mid\mid p(z)) \\&= \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{d} (1 + \log \sigma_i^2 - \mu_i^2 - \sigma_i^2)\end{aligned}\]The reconstruction loss is defined differently for Gaussian and Bernoulli output distributions. We will focus on the Gaussian form.

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{reconstruction}}(x,z) = -\mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x)} \left[ \log p(x\mid z) \right]\]In practice this is implemented as the MSE between the mean of the output \(p(x\mid z)\) and the input \(x\). We can expand the log probability as follows (\(\mu_q\) and \(\sigma_q\) represents the outputs of the decoder):

\[\log p(x\mid z) = -\frac{n}{2}\log(2\pi) - \frac{n}{2}\log(\sigma_q(z)^2) - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \mu_q(z))^2\]We can take the mean and drop the constants and optimize the MSE:

\[- \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \mu_q(z))^2\]The optimization process combines both losses as follows:

- Take a batch of input examples (images): \(x_i\).

- Use the encoder to generate mean and log variance parameters: \(\mu_i\) , \(logvar_i\).

- Sample \(\epsilon\) to generate latent embeddings \(z_i\) for each example using the reparameterization trick.

- Pass the latent embeddings through the decoder and take the mean of the output distribution or reconstruction: \(\hat{x}_i\).

- Calculate the reconstruction loss between the decoder’s output mean and the inputs \(x_i\). Calculate the KL loss using the mean and variance from the encoder. Sum these losses and backpropagate through both networks.

Generation

To generate examples with a VAE, we only use the decoder. First, we sample \(z\) from the prior \(p(z)\), which is set to the unit Gaussian. This sampled value passes through the decoder to produce the distribution \(p(x\mid z)\), which can be either Gaussian or Bernoulli. For images, we typically don’t sample from \(p(x\mid z)\) since it represents pixel-level probabilities and sampling from it would only add noise. By sampling different values of \(z\), we can generate diverse images.

ELBO

The loss we defined for VAE is known as the Expected Lower Bound (ELBO). This can be formulated as follows:

\[\text{ELBO} = -\mathcal{L}_{\text{reconstruction}} + -\mathcal{L}_{\text{KL}} = \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)}[\log p(x_i\mid z)] - \text{KL}(q(z\mid x_i) \mid\mid p(z))\]We take the negations of the losses for ELBO because it is a lower bound that we want to maximize through gradient ascent. However, in practice we may just minimize negative ELBO.

We have arrived at ELBO from a practical standpoint. This can also be derived through variational inference. We will now go deeper into the mathematical intuitions of ELBO and VAE.

We can start by considering training the decoder by maximizing the likelihood:

\[\mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \left[ \log p (x_i, z) \right]\]This is intractable because it requires taking an integral over the continuous latent variable. Instead of optimizing the intractable likelihood, we can formulate a lower bound. Maximizing this lower bound is a proxy to optimizing the likelihood. Variational inference is a mathematical framework that approximates complex probability distributions by optimizing a simpler distribution to be as close as possible to the target distribution.

Derivations

In unsupervised learning we want to increase the probability of the data, which we express as \(\mathrm{log}(p(x_i))\).

We can first express the log probability as an expectation with respect to the latent variable. This is done by expanding \(p(x)\) as an integral over \(z\). We then multiply the numerator and denominator by \(q(z)\) and rearrange these terms:

\[\begin{aligned}\mathrm{log}(p(x_i)) &=\log\int p(x_i\mid z) p(z) dz\\ &= \log\int p(x_i\mid z) p(z) \frac{q_i(z\mid x_i)}{q_i(z\mid x_i)} dz \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} [\frac{p(x_i\mid z)p_i(z)}{q_i(z\mid x_i)}] \end{aligned}\]Jensen’s Inequality states that for any concave function \(f\): \(f(E[y]) \geq E[f(y)]\). This applies to the log likelihood because \(\log\) is a concave function. We can apply Jensen’s inequality to the expectation we have derived.

\[\log \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} [\frac{p(x_i\mid z)p_i(z)}{q(z\mid x_i)}] \geq \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \log[\frac{p(x_i\mid z)p_i(z)}{q(z\mid x_i)}]\]The quantity on the right represents the lower bound on the log probability. We can rearrange the terms on the right for a more interpretable formula for ELBO.

\[\begin{aligned} &\geq \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} [\log(p(x_i\mid z)) + \log(\frac{p(z)}{q_i(z\mid x_i)})] \\ &\geq \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \log(p(x_i\mid z)) + \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \log(\frac{p(z)}{q_i(z\mid x_i)}) \\ &\geq \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \log(p(x_i\mid z)) - \text{KL}(q_i(z\mid x_i) \mid\mid p(z)) \end{aligned}\]The first term is the reconstruction loss; the second is the KL term.

Alternative

It is also possible to derive ELBO from the definition of KL divergence. The first step to this derivation is the same. However, we continue by applying Bayes’ rule instead.

We start with the definition of KL divergence between the posterior and approximate posterior:

\[\mathrm{KL}(q(z\mid x_i) \mid\mid p(z\mid x_i)) = \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)}[\log \frac{q(z\mid x_i)}{p(z\mid x_i)}]\]Using Bayes’ rule, we can express the posterior as:

\[p(z\mid x_i) = \frac{p(x_i\mid z)p(z)}{p(x_i)}\]Substituting this into the KL divergence:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathrm{KL}(q(z\mid x_i) \mid\mid p(z\mid x_i)) &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)}[\log \frac{q(z\mid x_i)p(x_i)}{p(x_i\mid z)p(z)}] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)}[\log q(z\mid x_i) - \log p(x_i\mid z) - \log p(z) + \log p(x_i)] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)}[\log q(z\mid x_i) - \log p(x_i\mid z) - \log p(z)] + \log p(x_i) \end{aligned}\]We are able to remove \(p(x)\) from the expectation since it is the only term that doesn’t depend on \(z\). We can now rearrange the terms to isolate \(\log p(x)\). We want to place a bound on the quantity, like we did in the first derivation.

\[\begin{aligned} \log p(x_i) &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)}[\log p(x_i\mid z)] - \mathrm{KL}(q(z\mid x_i) \mid\mid p(z)) + \mathrm{KL}(q(z\mid x_i) \mid\mid p(z\mid x_i)) \\ &\geq \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)}[\log p(x_i\mid z)] - \mathrm{KL}(q(z\mid x_i) \mid\mid p(z)) \end{aligned}\]We drop the last term since KL is non-negative. We are able to get to the same lower bound.

Intuitions of ELBO

Now that we have derived ELBO, we will explain the intuition of its terms. We can first decompose the KL term.

\[\begin{aligned} \text{KL}(q(z\mid x_i) \mid\mid p(z)) &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \left[ \log \frac{q(z\mid x_i)}{p(z)} \right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \left[ \log q(z\mid x_i) - \log p(z) \right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \left[ \log q(z\mid x_i) \right] - \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \left[ \log p(z) \right] \end{aligned}\]The first term, \(\mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \left[ \log q(z\mid x_i) \right]\), is the negative entropy of the approximate posterior distribution. We want to increase the entropy of the decoder distribution so that we get diverse latent embeddings. This encourages the model to give probability to a wider range of latent embeddings and not overfit to precise values. This makes the VAE able to generalize better and make it easier to sample from.

The second term, \(\mathbb{E}_{z \sim q(z\mid x_i)} \left[ \log p(z) \right]\), is the cross-entropy between the approximate posterior and the prior. This term encourages the approximate posterior to be similar to the prior distribution. Since we typically use a unit Gaussian as the prior, this term pushes the approximate posterior toward a standard normal distribution. It is important that this distribution is close to the distribution we will be sampling from.

We use the reverse KL to strongly penalize \(q\) taking non zero values when \(p\) is zero. This encourages the supports of each distribution to be more aligned. We don’t want to generate latent embeddings during training that would be low probability during inference / generation.

Problems in VAE

Although it is a powerful architecture, there are several weaknesses to the VAE that follow up research seeks to address.

- Blurry images: VAEs tend to produce blurry output images due to their continuous latent embeddings.

- Posterior collapse: This occurs when the decoder ignores the latent embedding. If a decoder is too powerful, it can generate high-quality images without using information from the latent space. While this doesn’t harm image generation itself, it renders the latent embedding meaningless as a representation.

- Entanglement of the latent embedding: The latent dimensions in a VAE often become entangled, meaning that individual dimensions do not correspond to interpretable features. This makes it difficult to control specific attributes during generation or perform meaningful latent space manipulation.

β-VAE

This work by Higgins et al. 2017 explores a simple change to the VAE ELBO loss, by simply adding a weight \(\beta\) to the KL term of the loss:

\[\text{ELBO}_{\beta} = \mathbb{E}_{q(z\mid x_i)}[\log p(x_i\mid z)] - \beta\text{KL}(q(z\mid x_i) \mid\mid p(z))\]In the paper, they set \(\beta > 1\) and observe that it encourages more disentangled representations. This is because the prior \(p(z)\) is a multivariate distribution where each latent variable is completely independent of others. This also constrains the information capacity of the embedding, which forces the encoder to learn more of the underlying factors of the data. This is built on the assumption that disentangled representations are more efficient than entangled ones.

The authors point out that a latent embedding with independent factors isn’t necessarily disentangled. Entangled representations can be expressed as independent factors through PCA. We want these factors to be semantically interpretable.

Vector-Quantized VAE (VQ-VAE)

The latent embedding of the VAE is continuous. However, for some applications, we want to have a discrete latent representation. This can be used as categorical features in a downstream model. This can also be used for autoregressive modeling if the discrete values can be used to create a vocabulary.

van den Oord et al. (2017) introduce VQ-VAE to address this problem.

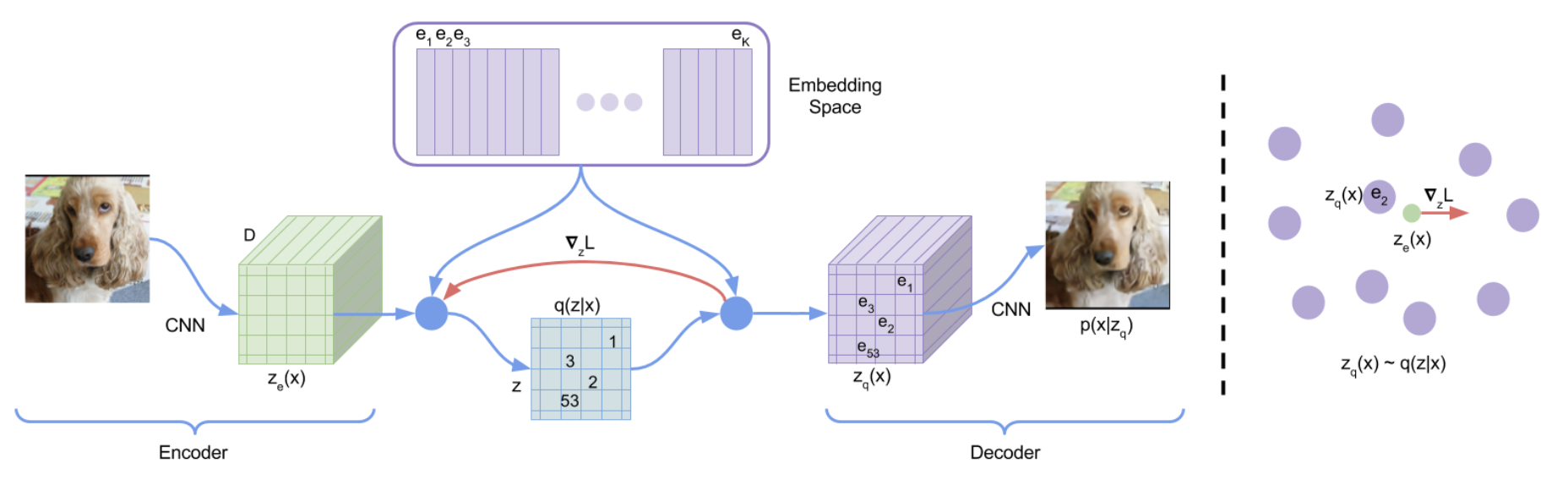

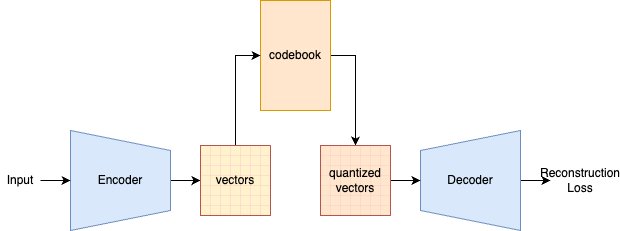

Forward Pass

- A CNN encoder maps the input image to a grid of latent embeddings. These are deterministic and do not require sampling through reparameterization.

- For each embedding, we find the closest embedding in the codebook. We replace the embedding with this codebook embedding.

- A CNN decoder reconstructs the image from the codebook embeddings.

The encoder generates an embedding \(z_e(x)\). This is matched to a codebook embedding \(e_j\). \(z_q(e)\) represents the quantized embedding. The encoder and quantization can be interpreted as a categorical probability distribution:

\[q(z=k\mid x) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{for } k = \text{argmin}_j \mid\mid z_e(x) - e_j\mid\mid_2, \\0 & \text{otherwise}.\end{cases}\]The decoder reconstructs the input from the quantized embedding: \(p(x\mid z_q(x))\)

Training

The VQ-VAE is trained with three loss terms:

\[L = \log p(x\mid z_q(x)) + \mid\mid\text{sg}[z_e(x)] - e\mid\mid_2^2 + \beta \mid\mid z_e(x) - \text{sg}[e]\mid\mid_2^2.\]- The first term is the reconstruction loss, which is used to train the decoder.

- The second term is the codebook loss which pushes the codebook embedding closer to the encoder’s output embedding.

- The third term is the commitment loss that pushes the encoder’s output embedding closer to the quantized embedding.

This loss term is meant to optimize reconstruction while also improving the quality of the quantization. There is no KL term as in the standard VAE. The second and third terms replace the KL term as it forces the encoder to match the prior of a categorical distribution.

We also want the quantization to be close to the prior, which is a uniform categorical distribution of the latent codes. We can consider the KL divergence of the quantized encoder with this prior:

\[\text{KL}(q(z\mid x) \mid\mid p(z)) = \sum_{z} q(z\mid x) \log \left( \frac{q(z\mid x)}{p(z)} \right)\]From the prior we get \(p(z=k) = \frac{1}{K}\). From the quantization operation we get \(q(z=k^*\mid x) = 1\) for some code \(k^*\), and 0 for all other values. We can use this to remove the summation.

\[\begin{aligned} \text{KL}(q(z\mid x) \mid\mid p(z)) &= \sum_{z} q(z\mid x) \log \left( \frac{q(z\mid x)}{\frac{1}{K}} \right) \\ \text{KL}(q(z\mid x) \mid\mid p(z)) &= q(z=k^*\mid x) \log \left( \frac{q(z=k^*\mid x)}{\frac{1}{K}} \right) \\\text{KL}(q(z\mid x) \mid\mid p(z)) &= 1 \cdot \log \left( \frac{1}{\frac{1}{K}} \right) \\\text{KL}(q(z\mid x) \mid\mid p(z)) &= \log K\end{aligned}\]We arrive at a constant value which we can ignore in the optimization. However, we still have a potential issue with VQ-VAE in code imbalance, where certain codes are used more often than others. This could lead to posterior collapse.

One important detail to note is that the quantization operation is non-differentiable. The authors use a straight through estimator to address this. This simply involves copying the gradients from the codebook embedding \(z_q(x)\) to the unquantized embedding \(z_e(x)\). As the model trains, these two embeddings become closer together and the gradients become more accurate.

Generation

In VQ-VAE we don’t sample from the categorical distribution of codes directly. The encoder maps each image to a fixed number of codes (ex: 128) with an order. We can use these codes to train an autoregressive model like PixelCNN. We can sample latent codes from this model through ancestral sampling. These codes are then fed into the VQ-VAE decoder to generate an image. VQ-VAE is powerful in that it enables usage of powerful autoregressive models. More recently it is common to use transforms to model in the latent space.

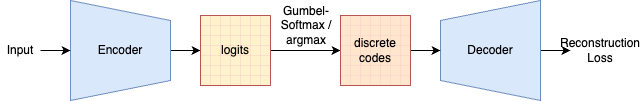

Discrete VAE

The discrete variational autoencoder (dVAE), used in OpenAI’s image generation model DALLE, provides an alternative to vector quantization. In VQ-VAE the encoder maps the images to a grid of vectors which are then quantized. In dVAE, the encoder maps the inputs directly to the discrete encodings. Instead of a grid of vectors, we get a grid of scalars.

The encoder first maps inputs to grids of vectors, as done in VQ-VAE. However, these are treated as one-hot encoding from a categorical distribution. The argmax is then taken to discretize this encoding into a scalar. These scalars can be auto-regressively modeled and then sampled from.

Gumbel-Softmax

In order to make this trainable, we use the Gumbel-Softmax relaxation. This relaxation for VAEs is introduced concurrently in the papers Jang et al. 2016 and Maddison et al. 2016 (Eric Jang blog post). The Gumbel-Softmax can be defined as follows:

\[z = \text{one_hot}(\text{argmax}_i[g_i+\log\pi_i])\]\(i\) is the index in the one-hot encoding, which corresponds to the number of discrete codes. \(\pi_i\) is the probability of code \(i\) in the encoding.

\(g_i\) is a sample from the Gumbel distribution, also referred to as Gumbel noise. It is sampled as follows: \(g = -\log(-\log(u))\) where \(u \sim \text{Uniform}(0,1)\). This is applying the reparameterization trick to sampling from a categorical distribution. \(g_i\) is analogous to \(\sigma \epsilon\) in VAE. This noise also makes sure that codes that aren’t the max are selected and trained on.

This argmax can be approximated as a softmax:

\[y_i = \frac{\exp((\log(\pi_i) + g_i)/\tau)}{\sum_{j=1}^{k} \exp((\log(\pi_j) + g_j)/\tau)} \quad \text{for } i = 1, \dots, k.\]During training the temperature \(\tau\) is gradually reduced. As it approaches 0, the softmax approaches the argmax. We can then use an argmax for inference / generation. The temperature is annealed during training and not used during inference. At inference, we also do not need to add the Gumbel noise.

dVAE and VQ-VAE are similar architectures with a key difference in how they discretize the data.

Conclusion

This blog post explained the evolution of autoencoders to variational autoencoders to vector quantized variational autoencoders. This just covers the fundamental mathematical intuitions. The VAE and vector quantization are malleable frameworks that can be used in a variety of settings and within many variations of architecture. The VQGAN builds upon VQ-VAE by adding a discriminator to improve the image generation. VQ-VAE-2 improves upon the original by using a hierarchical approach with multiple levels of latent codes to capture both fine and coarse details. Although these models are most known for image generation, they are also very useful for discrete representation learning. This blog post focuses on the VAE and the encoding of images. There are also methods of additional conditions to the image generation, such as text prompts.

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Bandaru, Rohit (Feb 2025). Variational Autoencoders: VAE to VQ-VAE / dVAE. https://rohitbandaru.github.io.

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{bandaru2025variational-autoencoders-vae-to-vq-vae-dvae,

title = {Variational Autoencoders: VAE to VQ-VAE / dVAE},

author = {Bandaru, Rohit},

year = {2025},

month = {Feb},

url = {https://rohitbandaru.github.io/blog/VAEs/}

}